Black sororities have been in the spotlight in recent months. But for generations, hundreds of thousands of Black women have proudly represented their sororities – donning their letters, giving back to their communities, and leading in the classroom, boardroom, and beyond. It’s undeniable that Black sororities are of significant importance, cultivating a legacy of sisterhood, leadership, and community among their members.

From the founding of the first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA), in 1908 to the present day, Black sororities have been “more than just organizations; they are lifelines for many Black women,” says Takiyah Poindexter, a media manager from Los Angeles. “Black sororities provide lifelong friendships, professional opportunities, as well as provide a sense of belonging that is enduring.”

“Black sororities have served as the bedrock of psychological safety and support to and for Black women.”

At the beginning of the 1900s, Black sororities and fraternities emerged at US colleges and universities to uplift the Black community as it dealt with ongoing inequities. These organizations became known as the Divine Nine, and today, they continue to create unbreakable bonds between Black women who share similar identities, cultures, and experiences. If they meet the membership criteria (including high academic standards), women typically join during their undergraduate years while at their respective college or university campuses, where Black sororities are unified under the National Pan-Hellenic Council.

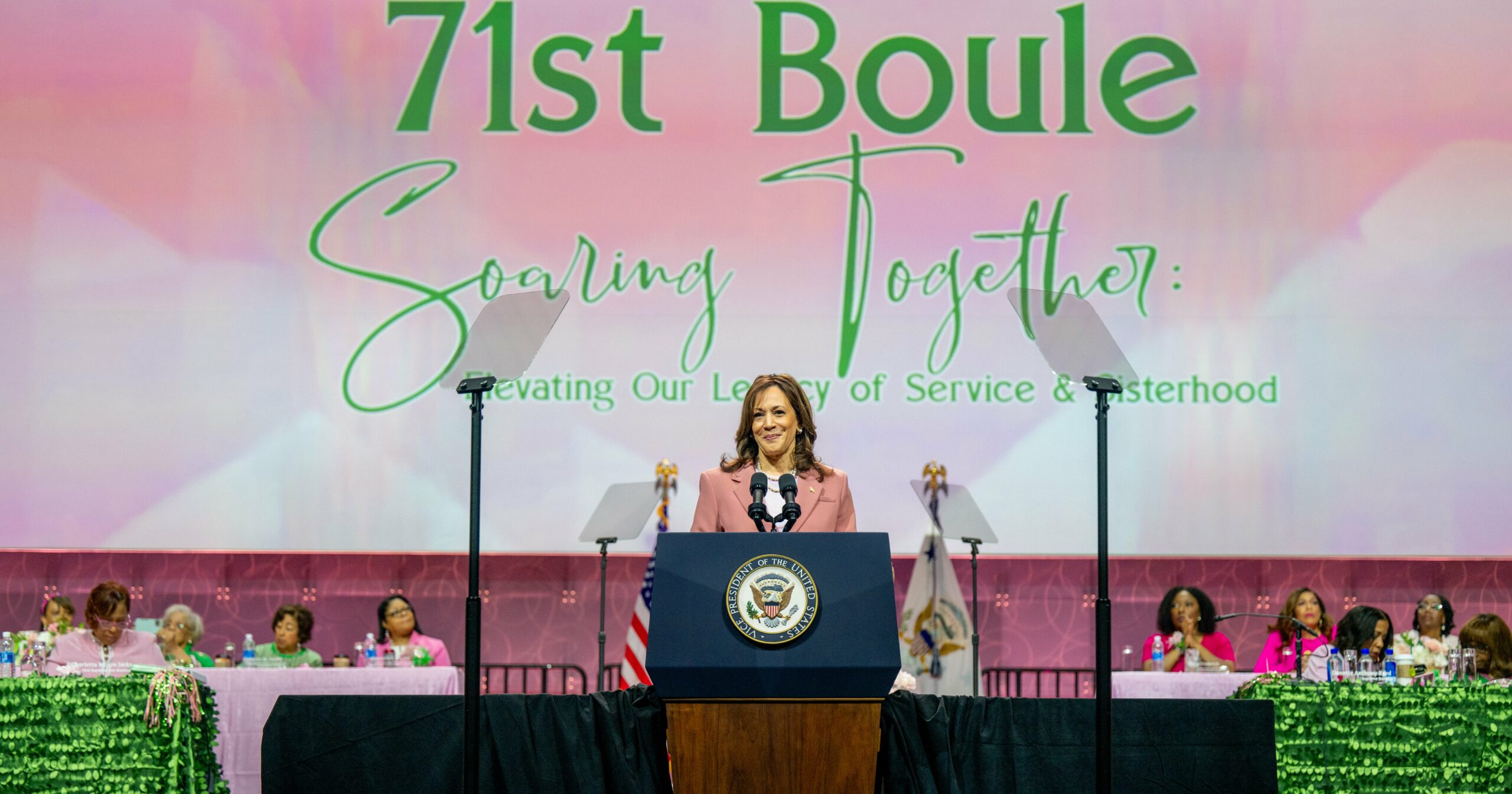

Many Americans hadn’t heard of or understood the significance of Black sororities until the ascension of Kamala Harris to the vice presidency in 2020. During her campaign, her famously green and pink sorority, AKA, along with other members of the D9, helped propel her to victory. After Harris officially kicked off her campaign for president in July, she specifically asked for support from fellow Black women at an address to members of the Zeta Phi Beta sorority in Indianapolis.

But on a more personal level, just as Poindexter points out, Black sororities are a lifeline for many Black women, myself included. I joined the illustrious sisterhood of AKA during my sophomore year of college, and it has given me so much – not only lifelong friendships, but also the best leadership training of my life. The lessons I learned through AKA have contributed immensely to the foundation of who I am as a woman, leader, and advocate for justice.

Our sorors (this is how we refer to our sisters) are a significant part of our big life moments, including graduations, marriages, births of our children, health crises like cancer, and the passing of our loved ones. At every turn, our sorors are with us, supporting and cheering us on.

This lifeline is crucial for our psychological well-being and mental health. According to psychologist and AKA member Camille Jones, PhD, fostering these close interpersonal relationships with folks from similar backgrounds “enhances overall well-being.”

“One of the best ways to practice self-care is to develop and maintain personal connections with others who provide emotional support,” she says. “Through both triumphant and challenging times, Black sororities have served as the bedrock of psychological safety and support to and for Black women.”

Community service is also a big reason many Black women join sororities, and that was the case for Poindexter, who joined AKA. She participated in an annual service project where sorority members mentored young girls. “Watching them grow and succeed, knowing we played a part in their development, was incredibly rewarding,” she says.

Tonya McKenzie, a public relations media expert and a commissioner for Los Angeles County, decided to join Zeta Phi Beta in 1995 because “seeing how people galvanized around Black leadership was inspiring to me,” she says. “The Black women I encountered were smart, dynamic, charismatic, and funny. The positive way they represented the Black community left an impression on me.”

“[T]he history embedded in our organizations cannot be erased.”

But recently, Black sororities have been in the spotlight for negative reasons. Earlier this year, a viral trend emerged in which some members of Black sororities denounced their membership, many of them citing conflicts with their religious beliefs. This rocked the sorority community, given that many women see their time in sisterhood as joyful.

Some current members saw the social media-based denouncements as attention-seeking or an attempt to diminish the significance of these organizations. “The recent controversy is complex. While media attention can amplify personal grievances, it’s essential to consider underlying issues such as evolving religious or personal beliefs, leadership disputes, or financial concerns,” Poindexter says. “Such incidents, even this controversial, do not tarnish the legacy of Black sororities; instead, they highlight the need for continuous improvement and open dialogue within these organizations.”

Educator Paula Hammond, a member of Delta Sigma Theta, recently saw a member of her organization denounce their membership. For her, the public denouncements are “disheartening.” “I don’t think there is one single issue behind it,” she says. “Members renouncing their membership is not new; however, it’s the public sharing on social media that is new.”

Despite the recent controversy, Black sororities continue to be a strong presence of connection and solidarity for many. As McKenzie puts it, “Black sororities are here to stay, and the future is bright. Black sororities will continue to lead in advocacy, making a global impact through our service, passion, innovation, and invaluable contributions to all fields, from STEM to politics, from education to media.”

But it’s not just looking to the future; McKenzie says that preserving Black history is also a huge reason these sororities continue to be so important. “The traditions and history of our organizations encapsulate a rich part of our cultural heritage,” she says. “No matter how many attempts are made to alter historical narratives, the history embedded in our organizations cannot be erased.”

Earlier this month at Alpha Kappa Alpha’s biennial Boulé meeting in Dallas, more than 20,000 AKAs gathered to prove the sisterhood is still going strong. And with the possibility of a member of AKA becoming the next president of the United States, the power of this sisterhood and its core values couldn’t be clearer. As Hammond notes, “As Black women, we continue to be visionaries and have the power to effect change globally.”

Ralinda Watts is an author, diversity expert, consultant, practitioner, speaker, and proven thought leader who works at the intersection of race, identity, culture, and justice. She has contributed to numerous publications such as PS, CBS Media, Medium, Yahoo Life, and the Los Angeles Times.