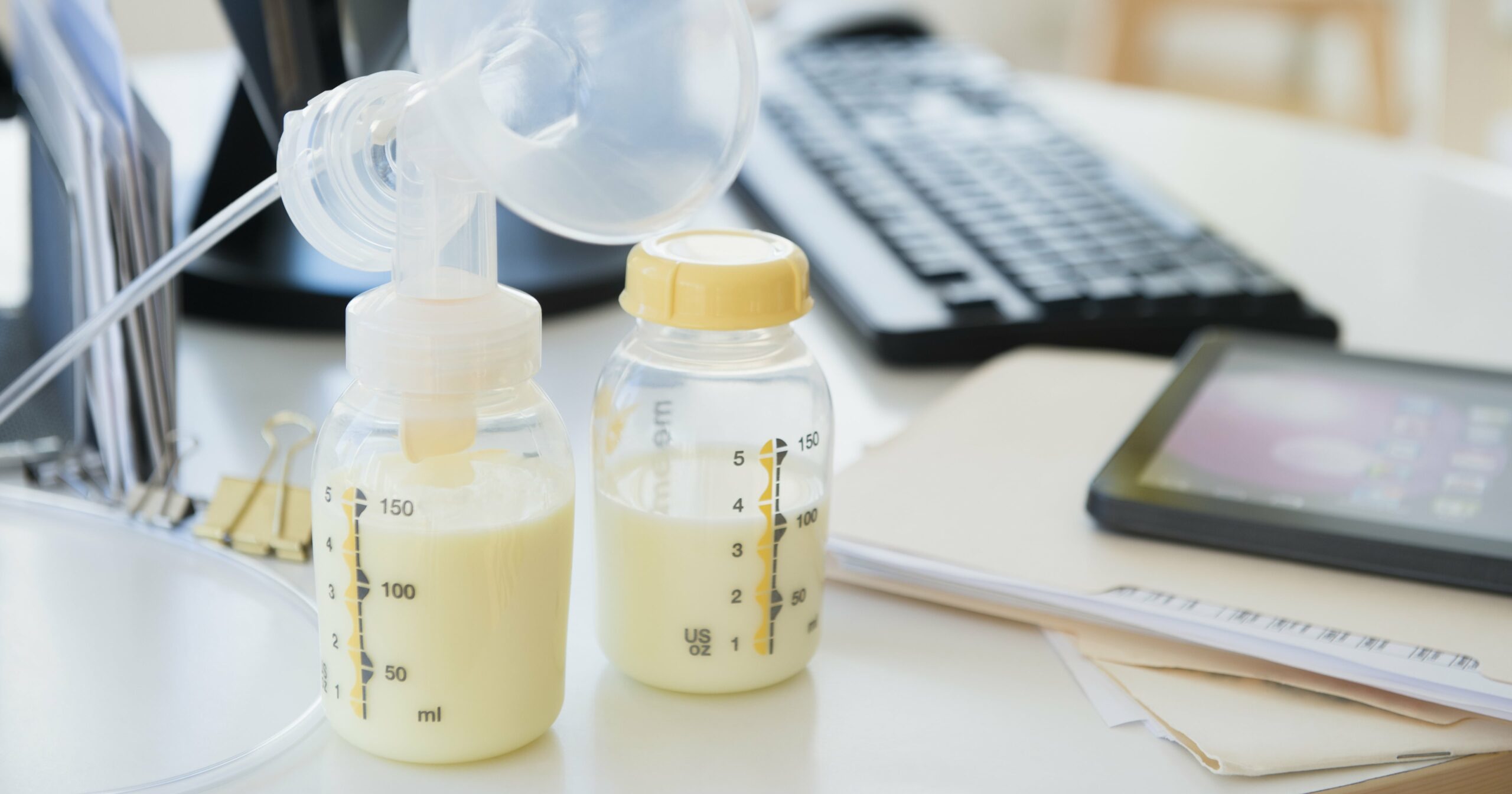

You’ve probably never heard someone describe breastfeeding as easy. Between latching issues, sore nipples, and generally feeling more cow than human, many new parents who choose to breastfeed their babies struggle. Heading back to the workplace brings a whole new set of challenges. Unless you work from home and have the flexibility to pump anytime, you’ll have to figure out how to get lactation accommodations like enough break time, a safe space to express milk, and a secure place to store it.

Fortunately, today there are multiple federal laws covering breastfeeding support in the workplace, and about 30 states have additional state-specific regulations. That means the vast majority of employees are guaranteed reasonable breaks and a private area (that isn’t a bathroom) to pump so that they can safely feed their baby the way they want without putting their jobs at risk.

Yet if a company hasn’t recently had a breastfeeding employee return to work, they might not be up to date on exactly what they’re supposed to do. “Oftentimes, employers want to accommodate, they just might not know what you need,” human resources professional Stephanie Reitz says.

As awkward as it might feel to bring up breast milk to your boss, if you want to nurse after returning to work, you might need to be your own advocate.

Experts Featured in This Article

Stephanie Reitz, MBA-HRM, is a human resources manager at MyHR Partner.

Cheryl Lebedevitch is the national policy director of the US Breastfeeding Committee, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

Athena Gabriella Guice is a full-spectrum doula and maternal health advocate.

Why It’s Worth Advocating For Lactation Accommodations at Work

The science is clear that breastfeeding provides multiple health benefits for both the baby and the breastfeeding parent. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for about six months, then continuing to nurse while introducing solid foods for at least two years. Even in the most generous circumstances, few working parents get quite that much parental leave, which means that if you want to go back to work and follow those recommendations, you’ll have to figure out how to pump on the job.

“If an employee is not able to express milk at work, it signals to the body that milk production can be reduced and can quickly compromise their milk supply,” says Cheryl Lebedevitch, national policy director of the US Breastfeeding Committee. Not being able to pump as often as your baby eats can also lead to nipple leaking or even infection, she adds.

Being able to nourish your child the way you want can also have a major impact on your mental health, points out full-spectrum doula Athena Gabriella Guice. “It’s just so deeply personal because we’re talking about bellies here. As a parent, to know that your child has nutrients and nourishment, it makes the biggest difference,” she says. Being separated from your infant when you return to work can already be a major strain; encountering logistical hurdles to breastfeeding because you need a paycheck only increases the risk of perinatal mood disorders, says Guice.

Sometimes, those hurdles become so challenging that parents give up breastfeeding sooner than they otherwise would have. One 2021 study on nursing parents in the journal Breastfeeding Medicine found that about 34 percent of those who didn’t return to work nursed for 12 or more months, while only 12 percent of those who returned full-time and 20 percent who returned part-time continued that long.

How to Advocate For Lactation Accommodations at Work

Reitz’s number one piece of advice for breastfeeding parents is to not be shy about your needs. “Take the time to look up your rights. Have a plan for what you need, and then present that plan to your employer, whether it be your HR representative or your manager,” she says. If you’re not sure what you’re entitled to, Lebedevitch says the nonprofits A Better Balance and the Center For WorkLife Law have free helplines to answer questions about your legal rights.

Start the conversation before you head out on parental leave. “Being transparent up-front helps a lot,” Reitz says. This gives your employer time to process your requests and make plans for the accommodations. Approach the topic by asking what the company’s lactation policy is, Reitz suggests. “Most organizations nowadays have one. And if they don’t, it’s an opportunity for education,” she says.

If you anticipate pushback, come prepared. Guice recommends getting a letter from your healthcare provider or your baby’s pediatrician if you think you’ll need it. You can also share the Business Case For Breastfeeding program from the US Department of Health and Human Services’s Office on Women’s Health, as well as the office’s series of videos on how various industries approach lactation accommodations.

Of course, before you’ve actually had your baby, you won’t know exactly how much break time you’ll need to pump, since it can vary from person to person (and sometimes pregnancy to pregnancy). So Reitz suggests checking in with your employer again a few weeks before you come back to share a better sense of what to expect.

What to Do If You’re Not Getting What You Need

Federal laws should give you the time and space you need to express milk. But certain employers, like airlines, railroads, and motor coaches, are exempt, and small companies can be excluded if lactation accommodations would be an “undue hardship” (though Reitz says that’s extremely difficult to prove). Even if you’re covered, however, that doesn’t guarantee compliance. Maybe the temporary lactation space is sometimes unavailable when you need it, or your manager pressures you to skip breaks during busy periods.

You may also want more than the minimum required by law. For instance, the Fair Labor Standards Act only covers one year following a child’s birth. If you want to breastfeed for the pediatrician-recommended two years, you’ll have to work that out with your employer – Reitz says most companies are open to it, since they will have already been doing it for months at that point and know what it takes.

If there’s no human resources department at your company, you may need to be assertive with your manager. Remember: you’re not doing anything wrong, you’re just reminding and educating them, Reitz says. If they’re still not following legal regulations, you could file a formal complaint with the US Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division.

“Don’t be afraid to stand up for yourself.”

Whatever you need to meet your breastfeeding goals while returning to work, the biggest thing to remember, Reitz says, is to not feel like you’re “putting someone out” for asking for what you need. “Don’t be afraid to stand up for yourself,” she says.

Even if your supervisor isn’t a parent themselves, they likely have someone close to them in their lives who is one, so you might come away from the conversation surprised by how willing they are to help you do what you need for your baby. “All we can do is try,” Guice says, adding that when you do that, “you’re able to go home and snuggle with your little one and just have that peace of mind.”

Jennifer Heimlich is a writer and editor with more than 15 years of experience in fitness and wellness journalism. She previously worked as the senior fitness editor for Well+Good and the editor in chief of Dance Magazine. A regular marathoner, she’s written about running and fitness for publications like Runner’s World, The Atlantic, and Women’s Running.