My partner and I once played a game where we tried to pinpoint the exact lyric from “The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess” that cemented our Chappell Roan obsessions. For him, the answer was obvious. He can never resist the cockeyed refrain in “Naked in Manhattan” when Roan implores a friend to “touch me, touch me, touch me, TOUCH ME!!” But I have a harder time narrowing it down. “Long hair, no bra, that’s my type” is an all-timer. I feel “Call me hot, not pretty” on a cellular level, like “girl math” but for flirting.

Maybe what hooked me wasn’t even a lyric, but the motorcycle rev in the first track, “Femininomenon” – a ridiculous, growly non-sequitur that’s a little boastful and obnoxious and totally out of the blue. It sets up an album that’s dripping with surprises, and one that’s been on constant repeat in my head ever since.

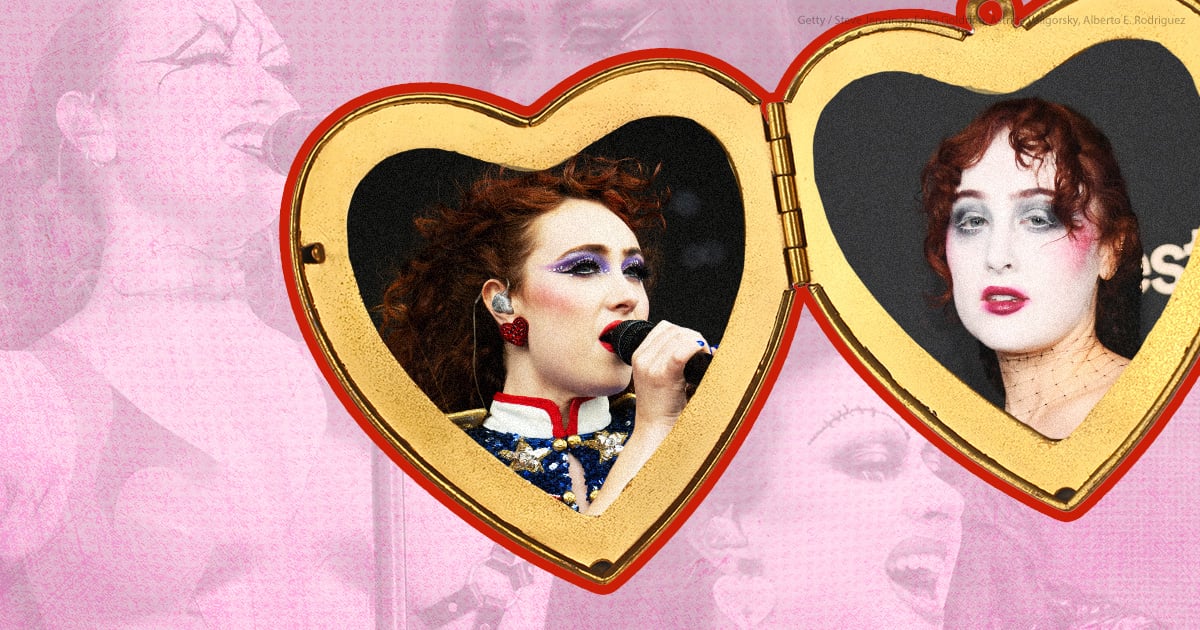

I’m clearly not the only bisexual who feels this way. The ruby-haired pop artist originally from Missouri has the world’s queers in a (consensual) chokehold, drawing record numbers to her festival shows all summer long, from Boston Calling to Outside Lands. “Midwest Princess,” her debut studio album, is approaching its one-year anniversary on Sept. 22, and sold its millionth copy at the end of August this year. But perhaps what’s most impressive is that Roan now trails Taylor Swift at number two on the Billboard 200 chart – all the more stunning after last summer’s Eras-mania that whipped the world into a blonde frenzy.

While everyone was shelling out their life savings for a chance to see the Eras Tour last summer, I was doing somersaults in my brain trying to figure out why I couldn’t relate. As much as I wanted to be swept up in the cultural moment, I didn’t feel anything. It wasn’t that I didn’t know a good chunk of her discography – Swift has been making commercially successful music since I was in sixth grade. I loved “Fearless” and “Teardrops on My Guitar” as much as the next romantically confused minor. But as Swift and I grew up, we grew in different directions. What I would learn about my body, my desires, and my politics made me feel I didn’t belong in a fan club that looked more like a Big Ten sorority than a women’s lib conference, at least from the outside.

If I wanted to be a superfan like the other girls, I would need a pop star who could bridge those worlds and others – someone to lace romance with rebellion, raunch, and raucousness. If I was ever going to feel anything close to Swiftie-level devotion, it would be for someone who’s tender and yearning but knows what she wants. Someone who shows the world how playful, how powerful, how multifaceted sapphic love is. Who wears her heart on her sleeve and blood red lipstick smeared all over her teeth.

For the first time in my life, Chappell Roan – in lots of tulle and drag makeup, in her miniskirts and go-go boots – has made me a stan.

I discovered her album a little over a year ago, as I was nearing the end of a relationship with a woman who ultimately decided she couldn’t split her focus between me and her PhD in robotics. Needless to say, the robots won. Several months earlier, I had ended a much more serious relationship with a big-hearted boy who, despite his best efforts, would never really understand my queerness. I had just moved into a new apartment with a friend I loosely had a crush on, my work life was unstable, and I was about to be love-bombed and ghosted by the most confused Tinder man ever to swipe right.

The walls of my metaphorical house were held together with masking tape. It was then that this tornado of a Midwest princess swept through, shattered the windows, leveled the ceilings, and broke something open in me that I’d been intermittently trying to access and snuff out since middle school: my desire.

For queers, the “sin” of our pervertedness is deeply ingrained. Messaging from all sides – media, lawmakers, neighbors with homophobic lawn signs – tells us we have dirty minds. That we want what’s unholy, unnatural, and unspeakable. Like so many young, queer people, I was bent in the shape of that shame. Roan throws her shoulder pads back, her cleavage high. I am perverted, she proclaims. I am kinky. I am feral. And aren’t I majestic?

Not only is Roan charting a new path for queer self-expression, she’s rewriting the rules of celebrity, asserting that her fame doesn’t make her public property. She recently posted a message on her social media firmly insisting that her fans give her space, treat her like a human being, and respect her privacy. “Women don’t owe you shit,” she wrote in her statement.

Core to being a Chappell stan – a Chaperone? A Pony? A Popstar? – are some of the most precious tenets of queerness: setting and respecting boundaries, protecting and uplifting ourselves and our communities, and being unapologetic about who we are and what we need.

In my current romantic relationship, a mutual Roan stanhood was one of our earliest points of compatibility. But once, for a past partner, I played Roan’s “Tiny Desk” performance on YouTube. She was good, he said, “but it’s just ‘girl music.'”

Yes, I said. Exactly.

Emma Glassman-Hughes is the associate editor at PS Balance. Before joining PS, her freelance and staff reporting roles spanned the lifestyle spectrum; she covered arts and culture for The Boston Globe, sex and relationships for Cosmopolitan, travel for Here Magazine, and food, climate, and agriculture for Ambrook Research.