It started as an innocent experiment. A chance to see what all the fuss was about – and whether a simple drug really had enabled hoards of Hollywood stars to shed tens of pounds seemingly overnight. That’s how the opportunity to test a form of the “miracle” weight loss drug GLP-1 (also known also as semaglutide, or by its most commonly-used brand names, Ozempic and Wegovy) began.

Truthfully, I knew very little about how the drug worked – all I believed, and cared about, was that it enabled users to slim down with what appeared to be minimal effort. “It just makes you eat less,” a friend who had been an early tester of Ozempic told me with a wink. Doctors don’t know how exactly the drugs – which are traditionally used to treat diabetes – lead to weight loss, only that they appear to help curb hunger and slow the movement of food from the stomach into the small intestine, which helps you to feel fuller faster. As someone who has always been the “big” friend – described as “tall,” “muscular,” and “athletic” rather than “petite,” “slim,” or “cute” – it didn’t really matter to me how it worked. Only that it did.

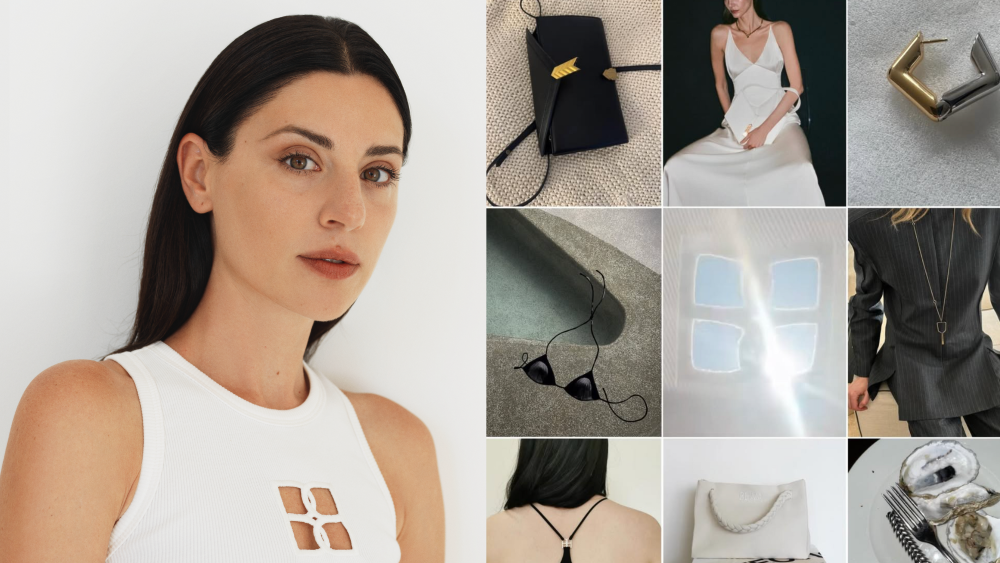

My introduction to GLP-1 came not long after Kim Kardashian’s now-infamous appearance at the 2022 Met Gala in that Marilyn Monroe dress. Her figure sparked speculation that she had turned to Ozempic to fit into the iconic gown (rumors that she has refused to address). In the years leading up to my GLP-1 trial, my weight had yo-yoed aggressively, and I was at a point where I was miserable with my appearance. It felt like no matter what I did, I would never be able to achieve anything near a “slender” figure.

When I arrived at the doctor for GLP-1 injection, I felt hopeful. No matter what, I decided, this would be the key to all my weight loss dreams.

Even after I began suffering from some awful side effects, I couldn’t be convinced that the drug was anything other than a miracle. Sure, eating full meals became impossible, leading to a fridge full of expensive leftovers and awkward plate picking. And yes, I did have to routinely run from the table to throw up after eating what the drug told my body was just a little too much food. I even refused to acknowledge GLP-1’s downsides after suffering a terrible bathroom accident in the office.

To me, these weren’t issues or difficulties – they were simply signs that the drug was doing its job. Because no matter how many ego-bashing incidents of vomiting or diarrhea I went through, the glow I felt every time I received a compliment about my weight loss couldn’t be dulled. Not a day would go by without being told how skinny I looked or how baggy my clothes had become. Comments that I brushed off in front of everyone who offered them but which stuck firmly in my mind. With every pound that dropped off my body, my confidence swelled just a little bit more.

After six weeks, my GLP-1 trial ended, and I was thrilled to see during my final weigh-in that I had lost 14 pounds. Publicly, I expressed relief that I’d finally be able to enjoy food once again, because I knew that’s what people would expect to hear. “Thank goodness that is over,” I told my ever-patient boyfriend. But inside, I was panicking. I was afraid of who I would be without the weight loss or without the attention that my shrinking frame attracted.

In the days after I stopped taking GLP-1, I still suffered from a few side effects. The constant feeling of fullness remained; my appetite was non-existent, and I’d get nauseous and vomit if I ate a full meal. Slowly, however, my hunger returned, and within a week or so, I felt my first stomach grumble in weeks.

To celebrate, my boyfriend took me out for my favorite (and oh-so basic) meal: a Caesar salad with a side of fries. The food arrived, and before I’d thought about it, my plate was empty. And I was disgusted with myself. I soon realized that without the safety blanket provided by GLP-1, my insatiable appetite had reared its ugly head and taken over.

A wave of nausea hit me as soon as I realized how much I’d eaten, and I ran to the bathroom to make myself vomit, convinced that if the food came up, the twisting in my stomach would go down. When I returned to the table, my boyfriend looked at me with concern. “I thought you were all better?” he asked. “Is something wrong? Should you see someone?”

I quickly brushed off his concerns, insisting it was nothing more than a GLP-1 hangover. But the truth is, over the next few weeks, I developed an increasingly unhealthy obsession with the idea that I “needed” to throw up any time I felt full.

I justified my behavior in all kinds of ways: I told myself that it was the ghost of GLP-1 keeping my appetite in check, that the drug had somehow trained my body to react this way when I ate to maintain my weight loss. My loved ones grew increasingly concerned about the fact that my so-called GLP-1 side effects were persisting and urged me to go to the doctor.

“I spoke to him, and he says it’s normal, and it’s not happening as much these days,” I lied, having just purged another meal. While I know now that they had the best intentions, at the time, their worry only motivated me to make one change – to hide the purging by whatever means necessary. I was convinced that they just didn’t understand and that keeping it a secret was easier than dragging out their fears.

This pattern continued for six months. Whenever I ate more than a few bites of a meal, a trip to the bathroom soon followed. I kept a list of excuses at the forefront of my mind at all times, ready to shut down any concerns that might be triggered by my frequent trips to the bathroom.

After a while, I struggled to remember a time when I hadn’t purged after a meal. And I really did believe that I could just carry on that way forever, acting – for the most part – like a healthy, happy 30-something while keeping my secret hidden from the world.

Believe it or not, that ridiculous illusion was only shattered by a trip to the dentist. She took one look at my teeth and the damage caused by my purging, and sat me down for a quiet word. “Your teeth have experienced some serious erosion since we last saw you, and I’m wondering if there’s anything you’d like to chat about. You aren’t under any obligation to speak to me, but if you’d like me to recommend a therapist who specializes in eating disorders, I can do that.”

Her words hit me like a bullet. I felt naked, exposed – and utterly ashamed.

A professional plainly stating how much damage I was doing to my body brought all of those justifications crashing down around me. I went home, collapsed in tears, and told my boyfriend everything. He helped me research eating disorder specialists, and within a week, I had started seeing someone regularly.

Six months later, I’m still very much in recovery. And, as anyone who has struggled with disordered eating will tell you, that process is likely going to last for the rest of my life. Looking in the mirror has become easier, but I still have days when a pair of too-tight pants makes me cry, or that extra-full feeling after a big meal leaves me desperate to flee to the bathroom.

I still don’t really understand how I allowed myself to fall down such a desperate and dark hole – however, Jennifer Rollin, LCSW-C, therapist and founder of The Eating Disorder Center, says that it is not uncommon for the use of weight loss drugs to trigger or exacerbate an eating disorder in patients. “Many eating disorders are triggered initially by a combination of factors, which can include genetics, psychosocial stressors, as well as attempts at dieting/restricting food intake/and weight loss. [So] it makes perfect sense that GLP-1 medications triggering nausea and vomiting around eating could lead to an eating disorder for those who are genetically predisposed.”

While my treatment is still ongoing, I try to claim a “win” each and every day. Enjoying a meal – rather than fearing it – is starting to feel like an achievement instead of a failure, and clothes shopping no longer fills me with a sense of dread.

My experience has taught me a great number of lessons, but what I know to be truer than anything else is that the conversations around these drugs and around our bodies has to change. Complimenting someone on their weight loss might seem like a kind act – but we need to ask ourselves the message that it sends, and whether commenting on anyone’s figure is “kind” – or just plain dangerous.