Visitors to the Rick Owens retrospective currently on at the Palais Galliera in Paris eventually arrive at a darkened room with a sensitivity warning, for it shelters a life-size statue of the designer relieving himself into a steel trough — and video footage of far naughtier acts.

And a conversation with the designer about his penchant for provocation ultimately alights on his infamous “free willy” men’s show for fall 2015, whose main feature was a visible penis, often peeping through portholes in cutaway outerwear.

Owens notes the spectacle riled Karl Lagerfeld, who denounced it as “disgusting” on French television.

You May Also Like

“I was delighted, because that’s exactly the kind of uptight white guy I wanted to provoke,” Owens recalls. “The world is such a judgmental place, filled with judgmental people like Karl Lagerfeld, that I feel my role is to playfully taunt them and promote my cheerful degeneracy to balance things out.

“I don’t want people to think there’s anything malicious in what I’m doing,” he stresses. “It’s just teasing, and it’s just kind of trying to balance out all this judgment.”

Owens confesses that some casting staff misconstrued his intention with that Full Monty show, expressing some remorse that “some of the members were not as impressive as they could have been.”

“This was not about porn at all. This was about treating penises so indifferently and casually, to make them lose their male sacredness, and to taunt masculine pride.”

Over a fashion career spanning more than 30 years, Owens has rebelled against intolerance and uptightness in all its forms, and become a cult fashion hero for his steadfast independence and highly original fashion vision, serving up bombast and a dash of transgression alongside his dignified, darkly glamorous designs.

“I do feel that the world always needs provocateurs. The world needs John Waters and Divine. The world needs David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, which at that moment was transgressive and shocking and horrifying,” he says. “When I saw those examples as a teenager, it gave me the strength to go on. It pulled me out of self-loathing. It pulled me out of shame for being a flamboyant child who was not in step with convention. So if I can be that for somebody, that will have been a life worth lived.”

Born in Porterville, Calif., Owens first went to art school, but then gravitated toward fashion, spending his first years as a patternmaker. His complicity with the know-how behind making clothes has been a defining feature of his career, leading him to Italy, his business partners, and the factory in Concordia, Italy, that turns out his signature label.

He calls himself a purveyor of slow fashion, insofar as he keeps hammering at the same aesthetic nails, and describes his career as a slow burn “due to my partners protecting me and allowing me to develop over a long period of time.”

His partners are Luca Ruggeri and his sister-in-law Elsa Lanzo, whom he initially met through the sales agency Eo Bocci and Associates, until they broke out on their own and devoted their efforts to the budding California talent. (Lanzo is chief executive officer and Ruggeri commercial director.) The three sussed out a factory in Concordia, brought on the owner as a fourth partner, and Owenscorp. was born.

“One of the keys to our success is the fact that I never had a design room in Paris,” the designer explains. “I went directly to the factory and made the samples with the factory that was going to produce them… It made us more streamlined, and it helped get stuff into the stores in a more timely fashion.”

Speaking over Zoom from his apartment in Lido, Owens confesses to feeling a great sense of completion with the Palais Galliera retrospective.

“It’s not like I’m retiring at all, but there is a sense of achievement, for sure, and also kind of thinking, What could possibly top that?” he says. “I have this sense that I’ve gotten more than I ever even thought about wanting, and that kind of recognition for somebody like me.”

Here, in his disarming, earnest drawl, Owens reflects on his latest career high, and the gradual steps that led to him becoming an integral part of the Paris fashion firmament.

WWD: Sorry to dwell on the question, but how are you going to top the Paris exhibition?

Rick Owens: I’m not somebody who hungers for more all the time. I’m skeptical of always needing something beyond the next horizon. I like to think of myself as somebody who is present and who is finding great satisfaction and looking around me and just thinking about things exactly as they are, and being just grateful for that.

I’m always suspicious of the greediness of the fashion world, that voraciousness, consumption, consumption, consumption and disposing, disposing and disposing. I know I make a lot of clothes that we ship and everything, but I do feel like I’m making stuff that will hopefully last for a long time. Quality is one of the most important things in life.

WWD: What is your earliest memory of wanting to be a fashion designer?

R.O.: I wanted to be an artist. I wanted to be Julian Schnabel, so I went to the Otis Art Institute of Parsons School of Design in Los Angeles. I remember we sneered at the fashion students for being too prissy in our grungy school, because we prided ourselves on being real artists and real painters. We were covered in paint, and we were grubby and grimy.

But after a couple of years, they gave us art theory classes that were so dense, complicated, elaborate and indulgent. This is my perception now. Back then I was very intimidated by them because I just thought, “Well, I don’t really have the intellectual stamina for this.”

WWD: So then what happened?

R.O.: I did the next best thing, as I always liked fashion and style, and was good with my hands. So I went to a trade school where I could learn to make patterns and did pretty well. I was very practical, and I thought if I get a skill, I’ll always be able to get some kind of job. I mean, being a fashion designer was a little too abstract, but to be able to go into a factory and be able to make clothes made more sense.

I found that thinking in 3D and working with patterns and sketches and selling all came naturally to me. So I worked as a patternmaker for three or four years, just working in factories, and it gave me an income.

And then at some point I thought, “OK, I’ve been comfortable for a while. Now I just need to go all punk rock, not worry about money.” I thought, “Maybe it’s going to be tough forever, but that’s OK, because now I’m going to be who I need to be, and it needs to be full-on. It needs to be hardcore”…. I always thought of Charles James, who had almost a mystical reverence for sticking to his exquisiteness, for sticking to his guns, and doing things his way, and living in kind of a squalor, but kind of a glamorous squalor, almost a monastic, elevated squalor. That was my big ambition.

WWD: What would you say was your biggest break as a fashion designer in the early days?

R.O.: I always credit (retailer) Charles Gallay. To have somebody with that discriminating eye endorse me was super encouraging. I brought him some clothes, and he agreed to buy the little collection that I had, paying 50 percent down and then the rest on COD, which is how I survived for a while. At the time he had three stores.

At some point he said, “You know, you should show your stuff in Paris. And if you go, I’ll introduce you to some people.” And that’s exactly what happened…. I started selling to Henri Bendel, Charivari, Joyce in Hong Kong. There was this network of fashion pioneers, so that enabled me to get an appointment with Mrs. (Joan) Burstein at Browns.

WWD: How did you end up leaving America and relocating to Europe?

R.O.: I was already spending so much time in Europe because manufacture, learning how to manufacture in Italy, it was almost impossible, waiting for samples in Los Angeles, going for a week in Italy, there was so much for me to learn on how to translate what I was doing into an industrial, Italian, industrial methods. So I ended up staying at the Italian factory a lot and and it just at one point, I just didn’t go back.

WWD: It sounds like you, Elsa and Luca are three musketeers.

R.O.: Elsa and Luca were there from the very beginning, and their ambition matched mine. They needed to make this work. They were hungry for this to be a success as much as I was. They had put all their eggs in one basket — mine. So all of us were just young and hungry and had the energy to be ferocious. It’s also kind of a love story, because this doesn’t happen a lot where the CEO and the distributorship and the production have all stayed together for a long time. It’s a very good, lucky marriage — and they are more, they are probably more talented than I am, finding ways to get the stuff sold and protecting me.

If I had worked for other houses, I would have disappeared a long time ago. I would have had my three years to prove myself and not been able to do it and thrown away. I was protected (by Elsa and Luca) and I was allowed to develop my voice over longer than three years. You know, there were moments probably where there wasn’t that much to sell, but they figured it out, and they stuck with me. We don’t see that kind of loyalty much these days.

WWD: Do you feel like your career has been a slow burn?

R.O.: Yes, due to my partners protecting me and allowing me to develop over a long period of time. There was a minute where American Vogue offered to sponsor my first actual runway show… I had some trepidations, because I was very aware that my aesthetic was not going to be as exciting as others under the glare of a runway spotlight. The whole allure of fashion shows was something I wasn’t familiar with, how to create that magic. But I knew it’s a lifelong commitment. You can never, ever stop, because once you stop, people assume there’s something wrong and it stains your allure.

There were some bumpy moments where I feel like I was awkward on the runway, but just kept working and learning. And after a while, I felt like I kind of knew what I was doing, and then I started playing. I started getting more dramatic.

WWD: Indeed, you blossomed into one of the great showmen of Paris. What was the spark?

R.O.: I thought, “How can I show beauty and morality? How can I show beauty and behavior?” Instead of putting women in precarious positions and treating them like dolls, how can I address human conditions and a beauty that isn’t about lipstick, and more about beautiful behavior? That made me blossom, and I started doing things that were more risky and more extreme. The fog machines got bigger then, as long as we’re doing fog, let’s try fire. Let’s try hanging people upside down. Let’s go all the way. Let’s go hardcore. I had no idea that this was in me.

WWD: Have you ever contemplated selling your house, or held talks to sell a stake?

R.O.: Sure, I’ve thought about it, because there have been moments where I’ve had offers and I’ve thought if I were responsible and wanted to take care of my loved ones, this would be the way to do it.

This business is tricky, and you never know what’s going to happen. But then I also thought, “Well, everybody will figure out how to survive without me…” But I really don’t know what I would do with myself afterwards. I would be lost not having this sense of purpose, this calendar, this sense of urgency and this cycle of the runways, collection and seasons, I love it. I love that pace.

WWD: What’s the best thing about being independent, and the most challenging?

R.O.: Well, being able to take a nap every day is a luxury that really not that many people can afford.

I don’t know what the disadvantages are. There is stress, but everybody’s level of stress rises to their personal world. This last show leading up to the retrospective, and all of it happening at the same time was probably a little tiny bit more stressful than I’m used to.

I’m not somebody who’s going to collect cars, collect art or get a yacht or a private jet. That’s not my thing at all. The best things in life is learning things so I thought, I’m gonna learn French, it will be great.

WWD: How is that working out?

R.O.: Ostensibly, the reason for it would be so that I could speak French for the (exhibition) audio guide, because I thought that that would be the polite and gracious thing to do. Paris is offering you this retrospective, the least you can do is speak a little French somewhere.

I’m still flabbergasted at how little I have learned in all this time, how little I have absorbed. It’s a little humiliating, and humbling, which is probably not the worst thing.

As of now, I am still taking French and right now we are reading a biography of Jacques Doucet, who has always been a fascination for me. He owned all of this Eileen Gray furniture, some Brancusis and Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” He had this collection when it was all new. It’s not like this stuff had provenance or had mythology behind it. He had this discerning eye and assembled this group of things that became so important later on and so important for me personally. These are things that I personally have always loved.

WWD: Do you have any role models or mentors that have impacted the way you’ve designed your business and your career?

R.O.: I don’t know how other people build businesses. I worked with partners who are talented at distribution, at managing people and putting a team together. Esthetically, there’s Charles James, there’s Mariano Fortuny, there’s Madame Gres, and there’s Zoran. Do you remember Zoran? Henri Bendel had a Rick Owens area, and they also had a Zoran floor, and I thought that was the peak of avant-garde in those days. I was just so proud to be in the same store that sold Zoran.

WWD: Do you have specific ambitions in mind for your house?

R.O.: I can always get better. I That’s all I want to do. I just want to get better, and I’m going to keep going.

I’m not comparing myself to Marlene Dietrich at all, but I’m looking at her storyline. I’ve always been impressed with her whole trajectory. She emerges as very provocative and transgressive, and she champions an alternative universe with her sexuality. And she follows that for a while, but then the war arrives, and she devotes herself to morality by entertaining the troops. Very impressive. And then after that, she reduces her life to a cabaret act that is so restrained and so minimal and so focused, because she’s not a great singer. But the way that she’s able to take what she’s got, her allure, her discipline, her rigor, her pacing, her intonation, her theatricality, and focus it into something magic that is fantastic, the way that she was able to do all of those things.

I’m thinking, “Am I entering my cabaret moment?”

I didn’t commit myself to moral duty a sliver as much as she did, but I, I was aware of what I was contributing morally to the world. I did take that seriously. I did take that into account.

You can’t stay the same forever, and you have to — dare I say it? — age gracefully. This is another period and how do I, how do I do that in a graceful, convincing and authentic way? So stay tuned.

WWD: Speaking of morality, during the pandemic, you were probably the only designer who showed models in face masks. How come?

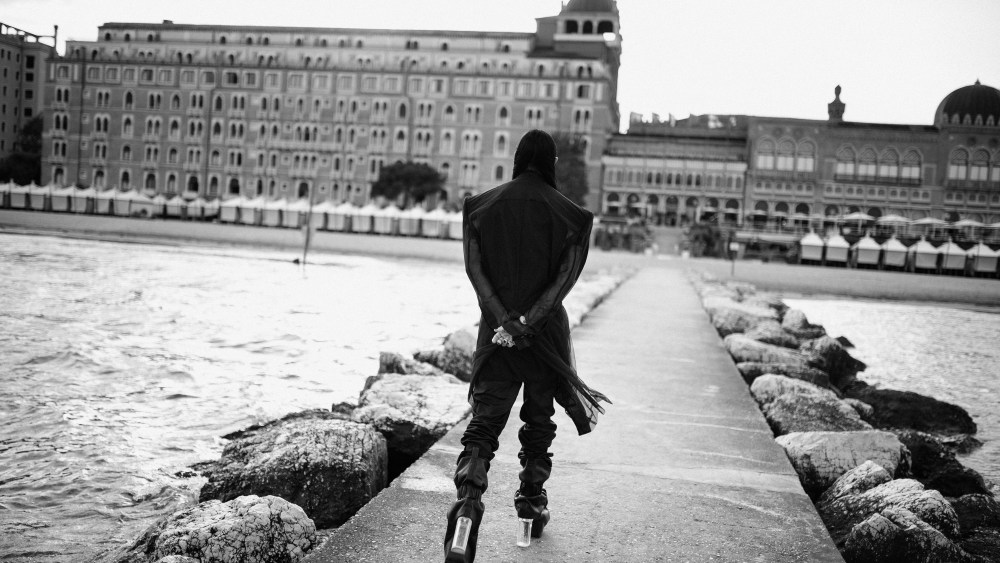

R.O.: We retreated to the Lido because it was a two-hour car ride from our factory, and we had the resources to be able to do runway shows, with no audience, with our skeleton team from Concordia.

We are in a period that was very threatening, and we didn’t know where it would end. But how you handle adversity defines somebody’s character, how one rises to the occasion and does their very best in that situation. That is beautiful behavior. How could you not show face masks during this moment? And those were some of my favorite shows. It was very bonding for us all.

WWD: Any other proud achievements?

R.O.: I’m here on the top floor of this apartment overlooking the sea, with Venice a five-minute boat ride away — and I don’t know how I got here.

I’m having such a quiet self-care period and I feel this tranquility with that retrospective, it really does feel like a different era. It really feels like such a resolution, but at the same time, I am working on women’s runway, and believe me, I have as much fire in my belly to do good things, if not more. I feel the same ambitious urge to just do the best stuff that I can, and to get better and to try and get someplace magic.