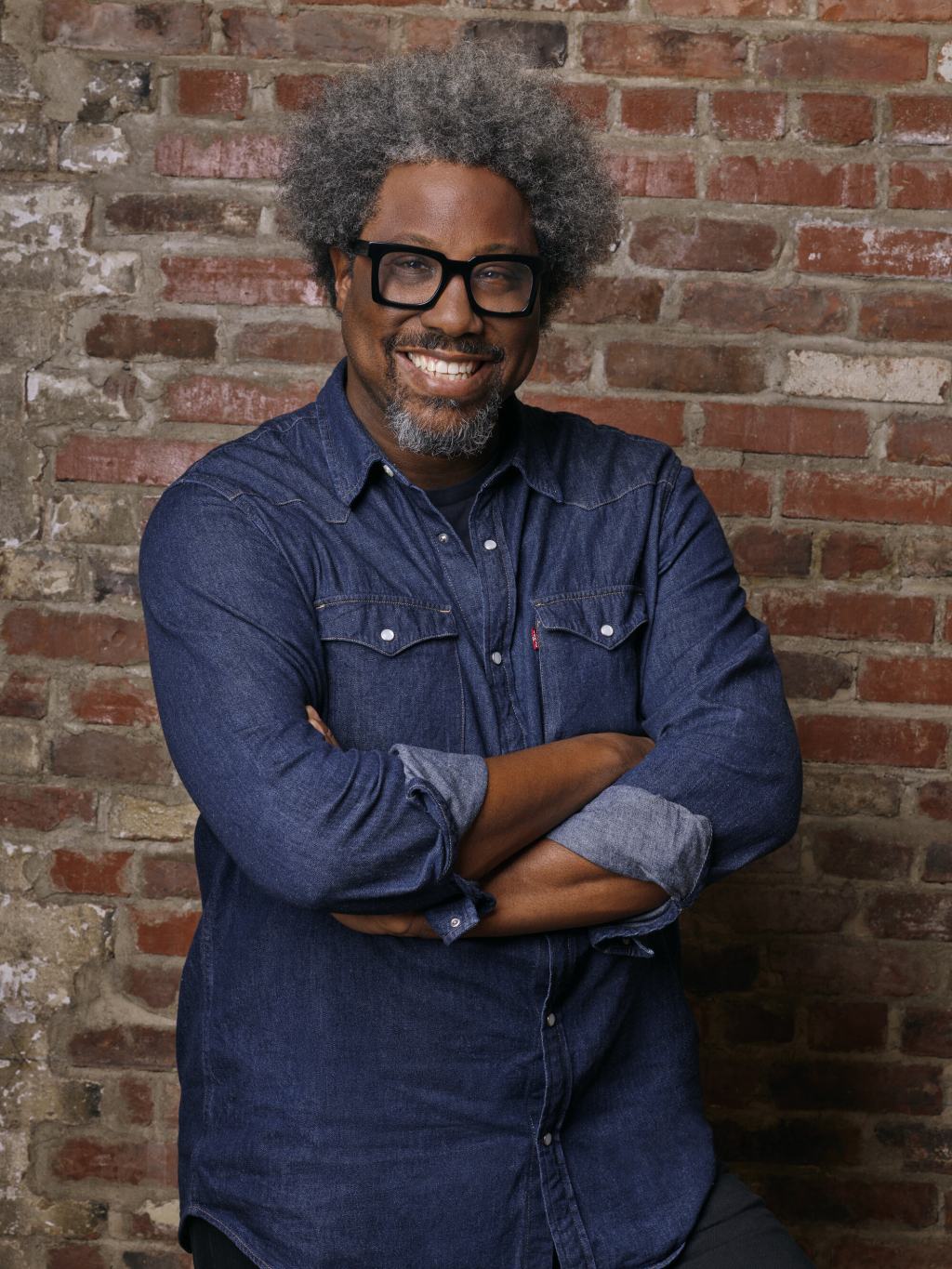

W. Kamau Bell cares very deeply about the state of the world. Whether he’s musing about raising mixed race children (he has three daughters ages 12, nine and five with his wife Melissa Hudson Bell, who is white), or formative childhood years in deep south Mobile, Ala., (from where his father’s side of the family hails), or talking about the current state of America’s fractured politics (with his good friend Hari Kondabolu on the “Politically Reactive” podcast), Bell’s brand of activist comedy strives to inform as much as entertain.

His CNN travelogue program “United Shades of America,” which wrapped in 2022 after seven seasons, allowed Bell to explore thorny social issues free from the punch-line imperatives of standup. And for much of 2021 he was working on his four-part documentary “We Need to Talk About Cosby,” which ran in early 2022 on Showtime and examined the crimes of Bill Cosby through the lens of fandom and how Cosby’s status as a pioneering Black comedian bumped up against a public reckoning.

In January, Bell began writing his “Who’s With Me?” Substack in response to the toxic spiral of social media. He notes that Substack — the subscription writing platform — reminds him of the early days of the internet when people actually shared ideas, instead of shouting each other down.

At the time of a recent Zoom interview, Bell is at the tail end of an eight-show standup residency — called “W. Kamau Bell Gets His Act Together” — in Berkeley, Calif. The shows have allowed him to workshop material for an anticipated standup tour in 2025, after what is shaping up to be a harrowing presidential election. It will be his first standup tour since he stopped performing at the outset of the pandemic. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to go to a basement club with low ceilings and have people breathe in my face,” explains Bell, who has asthma.

And this season he joins the long-running ABC program “What Would You Do?” The show, which is in its 17th season, sets up uncomfortable public scenarios and films unsuspecting bystanders as they interfere (or not) to voice their opinions about the injustices unfolding in their midst. The ruse is revealed when host John Quiñones emerges from behind the proverbial curtain with a camera crew in tow. Bell has a supporting role as a special correspondent, which means he pops up in the Quiñones role, playing a sort of puppet master as hired actors play out racist, sexist or dishonest scenarios to see if onlookers will intervene. (“The View” cohost Sara Haines also joins the show as a special correspondent.)

All of his work on “What Would You Do?” is in the can. He filmed scenarios in Florida and Alabama and will appear in several episodes. (“What Would You Do?” airs Sunday nights on ABC and also is available on Hulu.) There are several scenarios in which people, played by actors, can’t pay for things, whether it’s a pregnant woman who can’t afford the sausage, egg and cheese bagel she ordered or a dad who doesn’t have enough money for his daughter’s birthday present.

His first segment in Mobile, Ala., takes on hair discrimination. In the scene, a white woman asks a Black female job applicant to change her hair in order to secure the position. (Twenty-four states have codified the CROWN Act, which prohibits hair-based discrimination at work and school, but Alabama is not among them.) Bell notes that not all of the scenarios in which he appears are race based. And at least one was inspired by his own experience; a couple (actors) discuss the merits of vasectomy at a barber shop in Florida. Bell underwent a vasectomy after the birth of his third daughter, at the behest of his wife. He talked publicly about their debate and his own fears and misconceptions about the procedure. “Wooh!” he says, exhaling deeply. “That was a fun one to be a part of.”

For Bell, who has made a career out of having difficult conversations (with humor), working on “What Would You Do?” spurred “a roller coaster of emotions,” he says. He described the show as akin to MTV’s “Punk’d” if it were hosted by Dolly Parton: “Everybody involved would feel good at the end instead of just pretending to feel good for the cameras.”

Here, Bell talks to WWD about comedy in the era of anger, the effect of the racial reckoning on Hollywood projects and why he was quick to say yes to “What Would You Do?”

WWD: What did you know about “What Would You Do?” before ABC producers asked you to join? And what did you learn in the process of doing the show?

W. Kamau Bell: It’s one of those shows I would stumble across on TV, flipping channels, back in the days when we flipped through channels. And also, it’s become so big online and on YouTube and social media. One of my best friends who’s a comedian, Hari Kondabolu, he had always said, “One day I want to be the host of ‘What Would You Do?’” So one of the first calls I made once I got [this job] was [to Hari]. I was like, “Hey, man, I got some good news and bad news…” I think it’s a great testament to John that he and the producers identified people they thought would play well in their world and I was one of those people. I didn’t audition for it. I didn’t submit for it. I didn’t say I would do it, if you asked me. They just reached out and said would you be interested in doing this? And I was very quickly like, yeah! [The show] is both fun and funny. It’s funnier than a lot of the work I do but it’s also very meaningful. The reason why I think it’s so shareable on social media is it’s very heartfelt. In a very short clip, you go through the whole range of human emotions, and at the end of the clip you usually end up feeling better about the state of the world, which is not like most clips you see on social media.

WWD: Oh, so true. Sadly.

W.K.B.: What did you ask me?

WWD: What did you learn?

W.K.B.: Right! I learned that, even though I know the scenarios are fake — I’ve met the actors, and I’ve talked to them — I would get caught up in those moments, just like people watching at home. I’m there as a surrogate for the audience. I’m there with you feeling all the things you’re feeling.

WWD: The culture has shifted from the time this show started. People are very pissed off. There’s more gun violence. I’m sure the production is buttoned up. But do you ever feel vulnerable in these scenarios?

W.K.B.: ABC knows what they’re doing. I’ve never felt unsafe in any scenario. I felt way less safe on episodes of “United Shades of America.”

WWD: You said that most of the time people do the right thing. Does that surprise you given how angry and divided people seem these days?

W.K.B.: It’s not just that. There’s also a culture out there of people doing things for attention. So you have to sort of get their buy in, like, this is a real thing that’s happening. And then you go, it’s not a real thing. There’s a whole culture of what they call IRL streamers, in-real-life streamers. Their whole thing is to go out into the world and just cause mess and cause confrontation. So people are aware there are people out there just causing mess and confrontation, maybe for social media, and maybe just because they’re doing it. I think that’s the thing that maybe stops people from getting involved quicker, because their spidey senses are up more now than they used to be.

WWD: Right, because they don’t want to be involved in a prank that could go viral.

W.K.B.: Back in the day, it was like, “I don’t want to get involved because I don’t want to get sued.” And now it’s, “I don’t want to get involved because I don’t want to go viral.” Everybody’s going to whip out their phones if something happens and suddenly, you’re in the middle of a situation that is on the evening news. It’s like even if I would like to help that person, I don’t know if I want to get involved because of the consequences of getting involved. I would imagine the producers of the show who are planning these things are learning a lot about the difference between doing it now and doing it especially pre-COVID-19. We ran back to normal too quickly. And so everybody’s now 10 percent feral.

WWD: Or 20 percent feral.

W.K.B.: Yeah, some people are 90 percent feral.

WWD: So do these interactions that you’ve had in parts of America — Alabama and Florida — do they provide you with any material at all or any insight for your comedy?

W.K.B.: My whole life I’ve traveled around the country. I was an only child in a single parent home. I was born in California, we quickly moved back home to Indianapolis, where my mom was from. Then she got a job in Boston and then she wanted to move to Chicago. And every summer I would go to Alabama. So I spent my youth traveling around. Then I became a standup comedian, which is like, “have jokes, will travel.” Wherever they will pay you, you go. At CNN, I spent seven seasons going to different parts of America. That has given me the perspective that America is not just one thing. I can basically be comfortable anywhere because I’ve seen enough to know how to be everywhere. I’m the guy who went to a Klan rally [for the first episode of “United Shades of America”]. So I understand how to maneuver around the world. That doesn’t mean I always feel safe. That doesn’t mean I always want to be where I’m at. I feel very blessed to know how to move around America in ways that I think most people don’t. Most people were born, raised and die in the same place. I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

WWD: You’re a topical comedian at a time when people are pretty much at each other’s throats. Is that a heavy load to carry?

W.K.B.: Actually, me coming back is more of an indicator of like, man, there’s so much to talk about out here. If there’s ever a time to be a standup comedian, and also be a person who cares about the world, it’s 2024. I don’t think every comedian is built to address these moments. The great thing about comedy, is you can be a comic who absolutely doesn’t talk about the state of the world and be valuable to people because you give them a way to not think about the state of the world. And then you can be the kind of comic who addresses the state of the world and helps people understand what’s going on. [When] Jon Stewart [went] back to “The Daily Show,” there was a collective reaction like, “Oh, good, phew, that’s where he’s supposed to be.” It just feels like where he belongs. I think Jon also recognizes if there’s ever a time to put the suit back on, it’s now. I feel glad that I came up in an era where there are more outlets for comedy because back in the day, if you didn’t get “Saturday Night Live” and you didn’t have a spot on a late-night talk show doing standup, you were sort of done. But I can turn on my phone and start right now. I feel glad that I’m alive during a moment where there’s more ways for people to get to you. I have a Substack now where I’m writing weekly in ways that I wouldn’t be writing if I hadn’t decided to do it myself. And as a parent of three daughters, who lives not in Hollywood or in Manhattan, but in Oakland, California, I’m out in the world all the time seeing the state of the world. So I happen to be a person who, if I wasn’t a comedian writing about these things, I would still care about the state of the world. I think it’s very natural for me to combine all those things.

WWD: OK, but do you sometimes wish you didn’t care so much?

W.K.B.: To be quite honest, it would be less stressful. I wouldn’t have to take all this blood pressure medication.

WWD: I remember talking to Jon Stewart at the end of his “Daily Show” tenure and he was pretty exhausted by it all. And Donald Trump had not even been elected yet.

W.K.B.: Ah, the good old days. This work can be exhausting. Now you can’t really complain about that a lot out in the world. I always joke that whenever I talk about how hard it is to be a comedian, the ghost of Harriet Tubman shows up and is like, “Oh, it’s hard to be a comedian….” But I understood when Jon Stewart stepped away. I empathize with the fact that he’d gone through a lot of cycles of electoral politics. And I can see him being like, “Do I need to go through this again?” The great part in him stepping away, was that it brought more voices out. We met Trevor Noah in ways we hadn’t met him before. John Oliver revealed himself to be this singular comedy force. Samantha Bee got her own show. All these voices on “The Daily Show” came forward. I think it showed people that there’s more than one way to do political comedy. When I had my first TV show called “Totally Biased” on FX, it was Stewart and [Stephen] Colbert. And then if you want to throw in Bill Maher, feel free. But that was basically it. Now you have Hasan Minhaj, you have John Oliver, Amanda Seales is on her Instagram talking politically. Even if you’re not on TV, the appetite for political comedy is at an all-time high. And it’s also not just a bastion of older white men.

WWW: OK, but a lot of women who had shows don’t have them anymore: Samantha Bee, Robin Thede. Do you really think that there are more and better opportunities now? Or do you think there are still only more and better opportunities for a certain subset of comedians?

W.K.B.: There are more opportunities. I can’t say they are better opportunities. At the end of the day, you still need to pay your rent or your mortgage and put food on the table. Comedians who address the state of the world, there’s not a lot of slots for that on mainstream outlets. If you don’t get to be the host of “The Daily Show,” you’re sort of out of the loop. You have to sort of go do it yourself. Now the great thing is you can do it yourself, it’s just harder that way. I’m super happy to have “What Would You Do?” Please, I hope they bring me back because it’s a lot of fun to do. But I’ve always got one foot [somewhere else]. I can’t just hope show business finds me a job. That’s why I started my Substack. I’ve got to always be thinking about doing it myself. If you’re a woman or a person of color, you always have to understand that the mainstream channels might mess with you for a little while, but they might not be permanently with you. I mean, even Issa Rae recently talked about [how she had to find] independent financing. And you’re like, if Issa Rae is talking about it, then what hope do I have.

WWW: The entire industry seems to be in a financial death shudder.

W.K.B.: America is going through a whole thing right now and show business being a part of America is going through the same thing. Who has the power, who has the money, who gets the power to greenlight things? And it’s generally the same people it has always been. In the post-2020 racial reckoning this country went through, there was a clamor for Black creators, specifically, to get more mainstream attention. And within a couple of years, a lot of that attention went away and a lot of those projects that were greenlit were suddenly not happening. That’s why I say as a Black person, or if you’re in the LGBTQ+ community, if you’re a woman, I mean think of Issa Rae or Ava DuVernay, at the height of mainstream success. And Ava DuVernay’s last movie [“Origin”], she had to raise independent financing.

WWD: When you started your Substack, you wrote that you felt the internet had become too toxic. How do you shield your daughters from social media?

W.K.B.: Me and my wife don’t want to totally shield them, especially my 12-year-old. I will ask, “Has your school taught you anything about what’s going on in the Middle East? Because I want to know what they’re saying and also, here’s my thoughts on that subject.” And they are aware of the world. When I showed my nine-year-old the clip of me on “What Would You Do?” from the hair discrimination episode, she grabbed my phone and ran to her older sister and was like, “I have to show you this.” They were in a discussion about how racist it was, and what people should do. I didn’t expect her to have that big of a reaction. But she’s like, I have to have a conversation with my older sister about this. Because they’ve talked about hair a lot obviously. They both know social media exists. I actually will save videos on Instagram to show them. They both have devices. I believe in having access to the technology. But it is the parents’ job to monitor that and so none of my kids have their own social media profiles, even though my 12-year-old is of the age where I’m sure she has friends who have [social media profiles].

WWD: Do you watch other comedians, or is that too much like work for you?

W.K.B.: I’m pretty comedy agnostic. I’ll watch 10 minutes of anybody’s comedy. But there are comics who are my favorites and people that I’ve known, that I’ve seen grow up in this industry. I’m always excited when they have new projects out. I’ve known Ali Wong since she started, so to see her [gain] great success, I feel invested in a way that I don’t feel with other comedians. I’m also old school enough that anytime Marc Maron does something — I’ve been following Marc since I was a teenager — I’ve got to go see it. I tend to watch comedy almost like it’s homework. If people are talking about a comedian’s special, even if I know I won’t like it, I have to watch it. Because I need to be aware of the conversation.