Fashion journalist Walter Greene, who supported and encouraged generations of Black creatives and models, died in New York on Dec. 2.

Funeral services are being planned for Greene, 74, who died in his Uptown New York City apartment. The cause of Greene’s death is not yet known, according to his niece Alana Doornick.

Without identifying the deceased by name, the New York Police Department confirmed that a 74-year-old male was found on Dec. 2 at the address, where he resided. A non-criminal investigation is underway.

Born in Guyana the youngest of five children, Greene moved to New York City in the early 1970s to pursue a career in fashion. After an early job at Mercury Records, Greene spent decades writing for Carib News, the leading weekly Caribbean-American news source in the U.S. He also worked with up-and-coming models and designers, and also worked behind-the-scenes on fashion shows by styling models and orchestrating the shows. He later freelanced for American magazines like Modern Luxury’s Edition, Essence, Sister 2 Sister, Odyssey Couleur and regional glossies.

His longtime friend Harriette Cole said, “Walter was a champion of people of African descent in the fashion world — designers, models, stylists and people behind-the-scenes. He sought out new Black talent to shine a light on them, when no one else was doing it. He kept track of all of the Black community in the fashion industry as they got much bigger. He was often the first person to do a story of a person of color in the industry before any of the mainstream publications were paying attention to them.”

You May Also Like

Tapping into another sector of fashion and style that more mainstream consumers disregard, Greene judged pageants for many years including ones throughout the Caribbean. He also taught models how to walk the runway, as well as poise and posture. That experience was the opportunity for many of them “to build a bigger life for themselves,” Cole said. To that end, the ever-gracious Greene always made a point of connecting people, but more in a salutary way than a pushy way. He would often say, “There is someone who I would like to introduce you to.”

Prior to relocating to the U.S., he designed clothing for members of his community in Guyana. Gentlemanly and supportive of Black creatives, Greene was a familiar face in the New York fashion scene, despite not having the automatic access or expense accounts that come with being affiliated with a major fashion media outlet. “In this industry that doesn’t pay that much attention to people of color, he worked so hard to make sure that people were seen and he did that with a smile on his face,” Cole said.

He came of age when there were few male Black peers save for André Leon Talley, Michael Roberts and Edward Enninful. In 2003, Greene was honored for his fashion journalism with a media excellence award at the Harlem’s In Vogue show in New York City. Years before diversity became a talking point and initiative in many corporations, he contributed to inclusion with his actions. Greene was also among the attendees at Jaguar’s 2010 Diversity Affluence event that honored leaders, achievers and pioneers in the fashion industry in the Hamptons.

Constance C. R. White said Thursday, “After being in the industry for so long, he just contributed so much. But not necessarily at the front-row, high-flying status level. He loved fashion and poured that into his work. He was consistently there, going to runway shows, speaking about what was happening in the industry, writing about it as a journalist and he also worked as a stylist.”

At fashion shows and work events, he dressed for the occasion often sporting a blazer even after dress codes became more relaxed. White said, “I think he was very conscientious of what he wanted to convey in an industry, where Black men could be typecast especially in the years that he came up. He had this gentlemanly thing about him, but he was still cool.”

Polite, courteous and respectful of people in the fashion business, regardless if he knew them personally or not, Greene was also “respectful of the work that was being done,” White said. “He was always coming at it as ‘This is important. This deserves attention, and the people doing this deserve respect.’”

Recalling Cole’s participation in a panel discussion with Greene at Pratt Institute in April that was part of the “Black Dress Talks” series that highlighted Black professionals in the fashion industry, she said that Greene “shared that while he knew that racism exists in fashion, he didn’t pay attention to that. He said he loved it and enjoyed every minute of it.”

Byron Lars, Tracy Reese and Patrick Kelly were among the designers that Greene championed, as well as Omar Salam and Diotima’s Rachel Scott. Lars described Greene Thursday as a “stalwart in the fashion trenches. No stone was ever left unturned by Walter, who gave equal reverence to the work of the power players and burgeoning designers alike. There was a hopefulness in his coverage of the latter that I always found endearing.”

Reese, the designer behind Hope for Flowers, recalled Thursday how Greene would send the press clippings of “the lavish coverage that he reported on” of her shows with a personal note. She said, “In an era when Black journalists were not always welcomed or respected, he always managed to show up, cheer us on and share our triumphs with the Caribbean diaspora. I will miss his gentle presence.”

Another designer Ralph Rucci praised Greene’s grace, humility and zest for equality in life especially in his profession. “He was a journalist who refused to participate in the politics of inclusion or exclusion. I respected him enormously for his knowledge and elevated viewpoint.”

Rucci’s sister Rosina added that Greene knew what had longevity and what would end up on discount stores’ clearance racks. She said, “He was also tireless in promoting the beauty of the Black woman and helped so many to feel beautiful and empowered.”

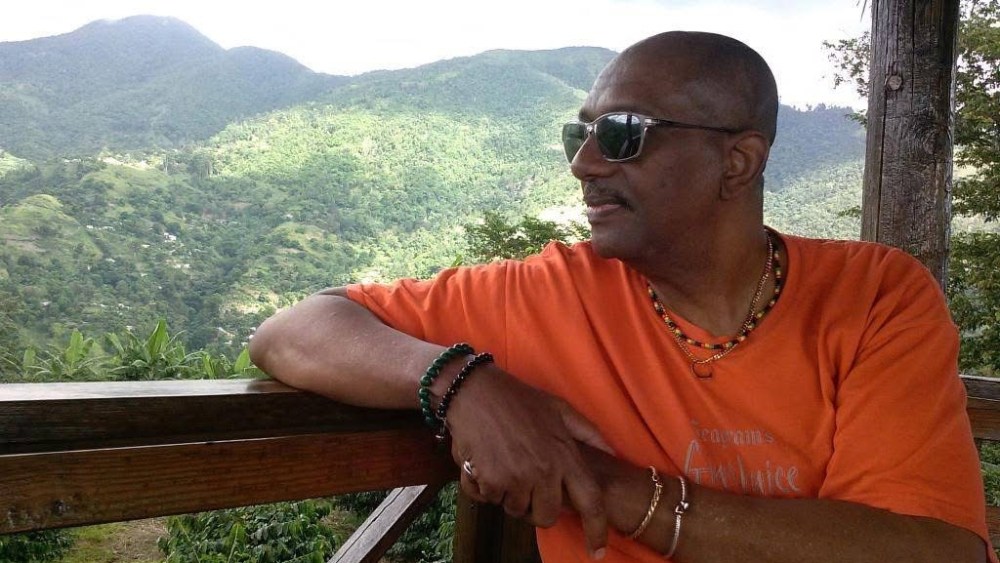

Greene liked to read mysteries and biographies, try new restaurants and in younger years run around the reservoir in Central Park and ride his bike in New York City. Travel was another favorite pursuit for Greene, with Jamaica being his go-to place. Once during a press trip to Francis Ford Coppola’s Blancaneaux Lodge in Belize, when the laughter from an after-dinner discussion made a neighboring table snicker and leave, Greene was unfazed. He said with a shrug, “We’re having more fun any way.”

Predeceased by his parents, and three brothers Richard, Winston and Ricky, Greene is survived by his sister Barbara Doornick.