NEW YORK — True to his precision as an editor, in accepting the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Sulurians Press Club Wednesday, Mort Sheinman didn’t just fact-check his career but he roused it to life.

During his WWD years — 30 of which were as managing editor — Sheinman helped transform what was then a daily trade newspaper focusing on Seventh Avenue into a lively publication that chronicled the intersection of fashion, pop culture, sports and the social movements of the day. As a writer, he churned out interviews with Sid Caesar, former New York City Mayor John Lindsay, author Tom Wolfe and cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead; penned travel pieces about far-reaching places like Nepal, and mentored generations of journalists.

Presenting the award, former editor in chief and 39-year Fairchild veteran Edward Nardoza described how WWD was “then a singularly quirky newspaper — eccentric, powerful beyond its size, serious and sometimes not so serious. But journalistically, when it came to global, influential, high-powered business, [WWD was] obsessive about accuracy and breaking stories.”

Sheinman recalled how in 2001 he had been bullied into coming out of retirement briefly to shepherd WWD’s 90th anniversary issue and how the industry had paralleled society through the 20th century — a fashion reporter traveling on the doomed Titanic delivered one of the first firsthand accounts of its sinking and a Berlin reporter had written about the Nazi intimidation of Jewish merchants in 1933. Coverage included sketches by Benito Mussolini about what a good Italian citizen should wear — togas, no surprise. Reports on glamorous designers, IPOs, clubby billionaires and the digital revolution eventually followed. Sheinman’s headline for his account of life in a rollicking newsroom: “’Ten Numerals. Twenty Six Letters and a Miracle Every Day,’” Nardoza said. “Forty years, Mort — that’s a lot of miracles.”

Describing the accolade as an unexpected honor, Sheinman thanked the crowd at the National Arts Club. In a Q&A with the New York Times’ Clyde Haberman, he said what had attracted him to join WWD in 1960 was the wall between editorial and advertising and how Louis Fairchild “backed up his reporters,” emphasizing their accuracy when challenged by any critics. “I found that to be true in very large measure and that’s what kept me there [until 2000], among other things,” Sheinman said.

Started as a quarterly in 1910, WWD became a daily with issue number two, Sheinman said. The Fairchild family always made a policy of not running editorials about politics or civic affairs, and declined to back any political candidates.

Openly humbled, Sheinman praised WWD’s legendary and feared publisher John B. Fairchild for his leadership and underplayed his own contribution to WWD during a 40-year run. Asked about Fairchild’s feuds with select designers like Geoffrey Beene, Sheinman said that stemmed from the designer complaining that the assigned writer was not senior enough to his liking. “In a way, I was OK with that. Of course, you don’t like to see anybody arbitrarily banished from the news columns if they were making news. We were there to report news, not to cater to anybody’s personal whims. There were feuds. Could he be fair? I guess that depended where you were standing at the time.”

Chronicling outrageously creative characters that populated the vast fashion world or circled its vast periphery has always been another pursuit, according to Nardoza. Henry Kissinger once told John B. Fairchild how the only time that his mother had commented about his press was when he was mentioned in WWD, which was often, Nardoza added. Fairchild had dubbed Kissinger “The Playboy of the Western Wing.”

Referencing Sheinman’s WWD clips, Nardoza shared his eloquent lede for a 1979 Wolfe profile that segued into insights about courage, adventure, new journalism, celebrity and the writing process. Wolfe had told Sheinman, “’Writing to me is like arthritis. It hurts every day.’”

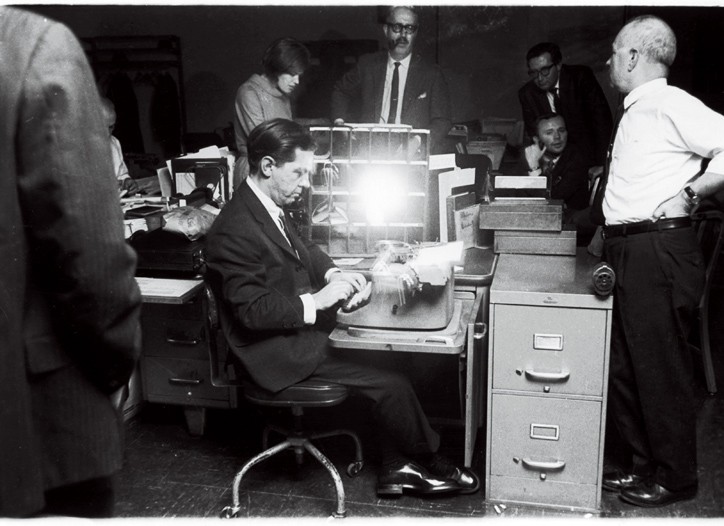

Describing Sheinman as “the gatekeeper, the deadline cop and standard bearer, pushing a crazy, chaotic, energetic newsroom to aspire to the highest journalistic ideals on the fly. He trained generations of reporters and editors — many of whom went on to populate the most influential magazines, newspapers and broadcast media around the world. When you hired someone from Fairchild, you got someone who could read a balance sheet, go deep on a fashion or cultural trend. Write a poignant obit. Write captions. Stage a shoot. Copy-edit a story or write a headline that fit,” Nardoza said.

Regardless if an article was about mobsters, mergers or wildly creative designers, Sheinman often stumped reporters with, “’How do you know this is true?’” Nardoza said. “If you couldn’t answer, you crawled back to your desk to start over.”

Making the point that Sheinman’s pussycat demeanor today belies his former self, in WWD’s case, the term “Mortification” could be used as a verb or an adjective, Nardoza said. The verb referred to the good part — the planning and rigorous editing for air-tightness and so that the copy might just sing, Nardoza said. Sloppy reporting, lazy thinking, blown deadlines, shortcuts, disrespect of a rich reporting tradition, dull headlines and cliches were off-limits. Sheinman later mused about how the garment district has changed, describing how decades ago a female worker was once flashed by a man in a raincoat. Her response was, “You call that a lining?”

Sheinman recalled editing an Alfred Hitchcock profle that started strong with the WWD reporter describing how the filmmaker had asked about the contents of his small shopping bag and was displeased with the response — a shirt. Impersonating the filmmaker’s distinctively throaty voice, Sheinman shared Hitchcock’s reply, “’No, a dead baby.” But the rest of the reporter’s piece was a “really boring promotional piece about the [director’s latest] movie,” Sheinman said. After calling over the writer and commending him on the lede, he told the reporter, “A great lede and then the rest of the story reads like a press release. You were with Hitchcock for an hour and a half. What else happened in that room?’”

After quizzing the reporter, Sheinman learned about other anecdotes, like how after Hitchcock’s PR stepped away in the name of hospitality, the filmmaker informed his guest, “’She’s going to poison your drink.’” Incredulous by the memory alone, Sheinman recalled, “I said, ‘Would you please go back to your typewriter and write that. Tell us more about what happened in that room.’ Sometimes when you’re an editor and you ask a reporter for more information, you come up with an astonishing story.”

He recalled how another WWD reporter, Madeleine Blaise, seemed to have the touch from the moment she was hired. But after assigned to WWD Eye’s section, her writing style changed dramatically — becoming more forced. Questioning Blaise about what caused the switch, he learned that Blaise mistakenly thought a certain stye was expected for her new post. He remembered, “I said, ‘Forget that. Write what you want to write and write it the way you write. You’re a terrific writer.’” Blaise went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing at the Miami Herald in 1980.