At Christofle, the silver lining is finally coming through.

After lackluster decades and disaffection, the French heritage silversmith has emerged from the pandemic with a fresh identity, a cheeky take on table manners and even a whole new collection signed by designer Aurélie Bidermann.

What changed?

Almost nothing, if its president and chief executive officer Émilie Viargues Metge is to be believed.

“All we had to do was go back to the origins, to the history of the brand,” she says.

And going back to square one is what changed everything.

When she took up the helm three years ago, the silversmith had “gone through three decades of disaffection for the arts of the table and silverware, which was perceived as old-fashioned — outmoded, even,” she recalls.

Despite regular injections from Dubai-based Chalhoub group, its parent company of 15 years and an investor for decades prior, the French company was hanging by a fork tine, with one French factory left to its name. Even its branding had been “blanded” close to oblivion.

Plus the COVID-19 pandemic had hit and wasn’t quite gone yet, although that eventually turned out to be a blessing of sorts as consumers took a greater interest in their homes.

Self-avowed “branding buff” Viargues Metge knew she needed an edge far sharper than anything in the Christofle inventory to cut it.

Help came in the shape of Ramdane Touhami, of L’Officine Universelle Buly fame, an “extraordinary, brilliant type” who she considers no less than “the genius of this century in terms of creativity and marketing.”

He agreed to take the brand on as the first client of his newly minted Art Recherche Industrie creative agency after the executive slid into his DMs on Instagram, because he too felt Christofle’s tremendous potential.

But by Viargues Metge’s account, the true architect of the brand’s resurgence is the man whose portrait now takes pride of place above the fireplace in the company’s Rue Royale flagship: Charles Christofle.

In 1830, the jeweler, who was “probably quite the extraordinary character given he was only 25,” according to the executive, founded his workshop in the metalworking Arts et Métiers neighborhood of central Paris, making it one of the rare luxury houses still existing today that was actually born within Paris.

Another brilliant move was the 1842 acquisition of patents for silver and gold metal electroplating, a more durable, safer and stable technique that allowed for production at scale, making Christofle the go-to brand for the rising bourgeois middle class of the Industrial Revolution who wanted to eat with silver-looking cutlery.

When Baron Haussmann redrew Paris’ cityscape, production moved outside of the French capital but Charles Christofle decided the smart move would be to set up shop on Rue Royale.

That brought him closer to his biggest client of the time, France’s Emperor Napoléon III and his wife Eugénie Bonaparte, “who was the foremost influencer of the time as all the European courts would envy and copy her style — and she knew how to spend,” says Viargues Metge.

As Touhami put it, “good old Charles was darned smart,” she recalls.

Take the house’s latest visual identity. Unveiled in late 2022, it feels more tweakment than reinvention.

That sage-going-on-olive green packaging with a creamy border? It’s “Napoleonian green,” she says, a color that nodded to its most famous patron but is also the one that best brings out the gold and silver of its craft. The typeface with its curling Art Nouveau flavor riffs off the original signature of the house.

And the crest surrounded by “Christofle, Orfèvre à Paris depuis 1830” combines the brand’s identity and history: scales used in the trade; two bees, marking it as a supplier of the French imperial court; three stars noting participation or wins at Universal Exhibitions, and “OC,” for Orfèvrerie Christofle (or “Christofle Silversmiths,” in English), the hallmark of the brand that signs each silver piece.

The strength of the house is not just its history but “retro-futurism,” she sums up. Case in point: The revamped Paris flagship on Rue Royale where new collections and reissues are set side by side in apothecary-style drawers.

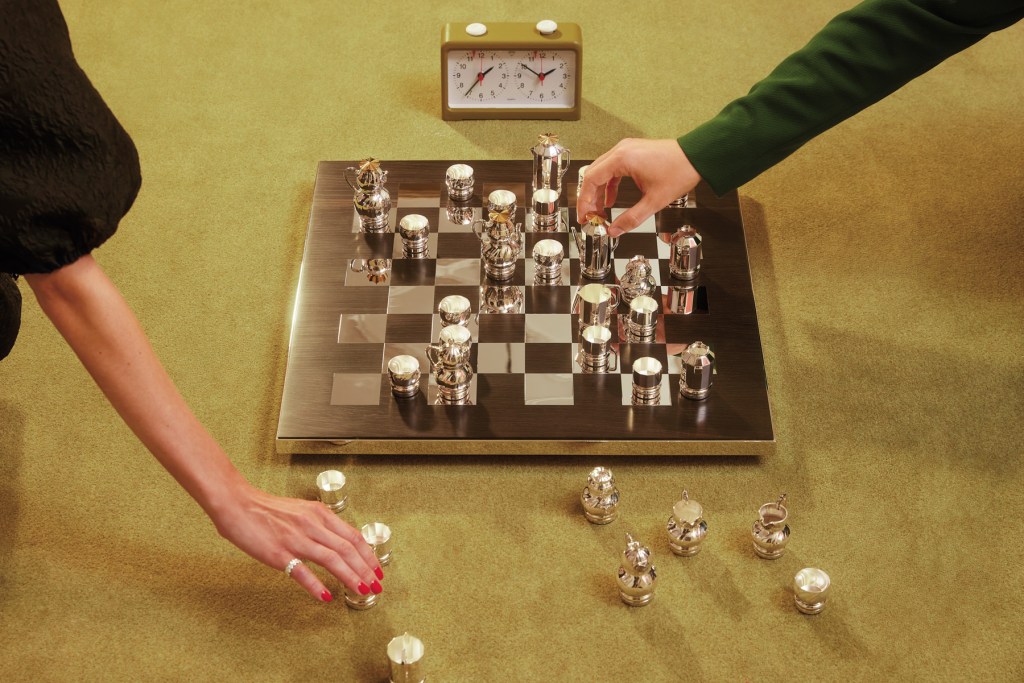

Also built into the new era was the notion floated by Touhami of “art on the table,” which became a motto, rather than the traditional “arts of the table” tenets of entertaining.

This took the house down a track that one could consider antithetic to the artisanal: NFTs.

For a luxury house, “it’s a gamble that puts you in danger,” says Viargues Metge. But for a house whose archives include pieces by artists like Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, Alphonse Mucha and Pablo Picasso, it felt fitting.

After all, NFTs “are contemporary art. You may like it or leave it, but it exists,” and it’s too soon to say who is tomorrow’s Jean-Michel Basquiat or a flash in the pan.

Not to mention the alchemical, near-magical process of silversmithing lent itself to being interpreted digitally, “a bit like one of the Brothers Grimms’ tales or Harry Potter,” she says, describing how the egg-shaped Mood collection served as the launchpad for a dive into house crafts.

That deep dive into the house archives also saw the return of the Gallia and Fjerdingstad sets as well as the introduction of a new streamlined 15-piece cutlery set titled “Infini.” In September came the Babylone collection, designed by Bidermann, who left her jewelry brand in late 2019 and now designs as an independent artist.

Given the sole brief of drawing up “a collection that would start with jewelry and continue on the table” with table decor and porcelain plates, the designer went for sensual roundness to evoke the generosity of food, soft volumes that evoke “a motif that unfurls like a ribbon,” but also the idea that the cuff bracelet, her starting point, is a shape that lends “strength and charisma to an outfit.”

For Viargues Metge, revitalizing the brand also means making it accessible, and that wasn’t a matter of price. It is high time for silverware to jump off its Sunday best pedestal and come out every day.

Case in point: The fish spoon. “Just imagine the love child of a spoon and a knife,” she describes. “As long as the object is beautiful and you’re getting a kick out of it, who cares if it’s bad manners to lick [cutlery],” she says with a genial shrug. “Let’s face it, the best part of a fish dish is the sauce.”

Also on the cards is a cleaning product that could make putting Christofle silverware through the dishwasher easy.

But if putting Christofle on today’s table is a priority, one growth engine has its roots firmly in the past: vintage pieces.

Hailing from the fashion industry, Viargues Metge initially wanted to set out ambitious sales goals. But given the artisanal and mostly handmade production, inventory would never be able to follow — or so she was told in an executive committee.

Her answer? “OK, if we can’t make enough product, let’s buy back our own,” she recalls. “After all, our real power is being able to say if an item is genuine Christofle or not, so let’s get them where they are.”

Plus “at some point, you can’t turn your nose up at vintage — it’s your products,” she adds.

Off the company went, scooping up pieces at estate sales and from auction houses like Christie’s or Drouot. Once certified, cleaned up, polished and silvered afresh as needed, they are put on sale under the “Vintage” designation.

Launched at small scale, the offering was an instant hit, says the executive, both for the company’s bottom line but most importantly, the emotional traction it found with consumers. “It was a ‘madeleine de Proust’ moment, with people stopping in front of the window. Grandmothers were pointing out items they’d received when they were children to their granddaughters,” she continues.

Now extended to the whole of Europe, the vintage offering is poised to jump across the Atlantic “soon,” promises the executive. “The U.S. is a market where anything antique is very much in demand — and there’s huge affection for Christofle.”

For now, the house is building inventory, with the introduction of a buyback program in November in France. “All you have to do is go to the site, send pictures. Once we have verified [authenticity], we’ll buy them online from you,” she says. “It’s a bit crazy for a luxury house to buy [its] vintage products online so it’s going to have some buzz to it. That’s novel but it’s also part of our retro-futurist approach.”

All in all, things are looking up and the house is already looking at regaining retail ground, with the overhaul of its boutique at Harrods, the second one to carry the refreshed identity after the Rue Royale flagship.

Plans are underway to revamp its Beverly Hills, Dubai Mall, Hong Kong and Rue Saint-Honoré boutiques. Three new stores are slated to open in Asia in 2024, bringing the brand’s number of doors to 52.

Even Charles Christofle’s oil portrait seemed to be pulling its weight. “Once we brought him back down [to the store], sales picked up again,” leaping a “never seen before” 52 percent in the space of two-and-a-half years, says Viargues Metge, although she declined to share sales figures. In 2017, the label had generated around 75 million euros in annual sales.

While the Europe, Middle East and Africa region remains in the lead, the U.S market comes a close second. “We were part of the first great movements toward the U.S. — on the Normandy, even on the Titanic,” owing to the lightness of its silver-plated items, she reveals.

According to the executive, most of the growth has come from new clients, while its historic client base has maintained itself. This has brought down the average age of the Christofle client from 50-plus years to a bracket between 35 and 38, who have been attracted to its jewelry lines, the new vintage offering but also gifting.

“Our accessibility is through gifts given or received, which proves the value of the brand. It adds something beyond the value of the item because you invest more in a gift, especially those around occasions,” Viargues Metge says, reminding that younger consumers often rate “meaning” highly in their purchasing decisions.

That’s a point that also resonates with Bidermann, who says that “when you want to pass an item on, it means it’s a quality object [imbued] with meaning” in tableware as in jewelry.

Being back on a growth track has also freed up headspace to think about what comes next.

First, there’s production. Currently, three quarters of Christofle’s items are done in France and 25 percent are done in Brazil, a historic production site that was sold but still works for the company.

While she hopes to reach 100 percent French production, the executive “doesn’t see a problem to delocalizing as long as it is intelligent” and keeps to Charles Christofle’s motto of “only quality: the best,” she says.

Already, the sole French factory, located in Normandy, has seen employee numbers grow from 200 to around 320.

One hurdle stands in the way — loss of know-how.

As it stands, too many of the techniques that made the success of the house, such as open fretwork that creates the impression of a metal filigree surface, have been lost. Even its silversmithing hallmark came close to disappearing at one point.

With no formal training or schools teaching them anywhere, the major three techniques still used today — chasing, embossing and leveling — are taught only internally at houses such as Christofle or Hermès-owned Puiforcat, pairing older craftspeople with younger generations.

But creating a Christofle training track or school isn’t enough. Viargues Metge is campaigning to have the resulting diploma recognized by the French state to give it measurable value.

And that’s a topic on which she won’t — or rather can’t — go at alone. Having reached out to other companies in the sector, including cutlery specialist Degrenne, crystalmaker Baccarat and family-owned porcelain manufacturer Bernardaud, she is adamant that they are “all fighting for a common cause: saying that French arts of the table are among the most beautiful in the world,” she says.

“At the end of the day, what matters is what we are transmitting to future generations,” continues Viargues Metge, the “37th president of Christofle and second woman” in the position. “I came for a job; I came away with a mission.”