Although Beatrix Potter may forever be tethered to the “Peter Rabbit” children’s book character that she created, her life’s work extended beyond that of an accomplished author and illustrator.

In addition to writing and illustrating 28 books ,including her 23 “Tales,” which have sold more than 250 million copies, Potter later became a farmer, sheep breeder and land conservationist. Potter, who lived in her family’s home near Sawrey, England, for the better part of the first 47 years of her life, also excelled in licensing. (Both of her grandfathers were established in their fields — one in calico printing and the other as a merchant with an inherited cotton mill.)

And a century before mushroom kawaii became a thing in manga and anime, Potter was an enthusiastic mycologist. So much so that she attempted to submit a scientific paper to the Linnean Society of London but was outright rejected (along sexist lines). As appears to be increasingly the case with Potter, she eventually got her due — in 1997, the Linnean Society’s executive secretary publicly admitted that Potter had been treated “scurvily.”

More recently last December, Potter was saluted for some of her drawings and studies of fungi that were considered to be decades ahead of scientific research. The earliest disease-causing fungus was named in her honor after it was discovered in the British Natural History Museum’s fossil collections. Who wouldn’t like a 407-million-years-old fungal plant pathogen — Potteromyces asteroxylicola — named in their honor? Potter also has an asteroid named after her, but we digress.

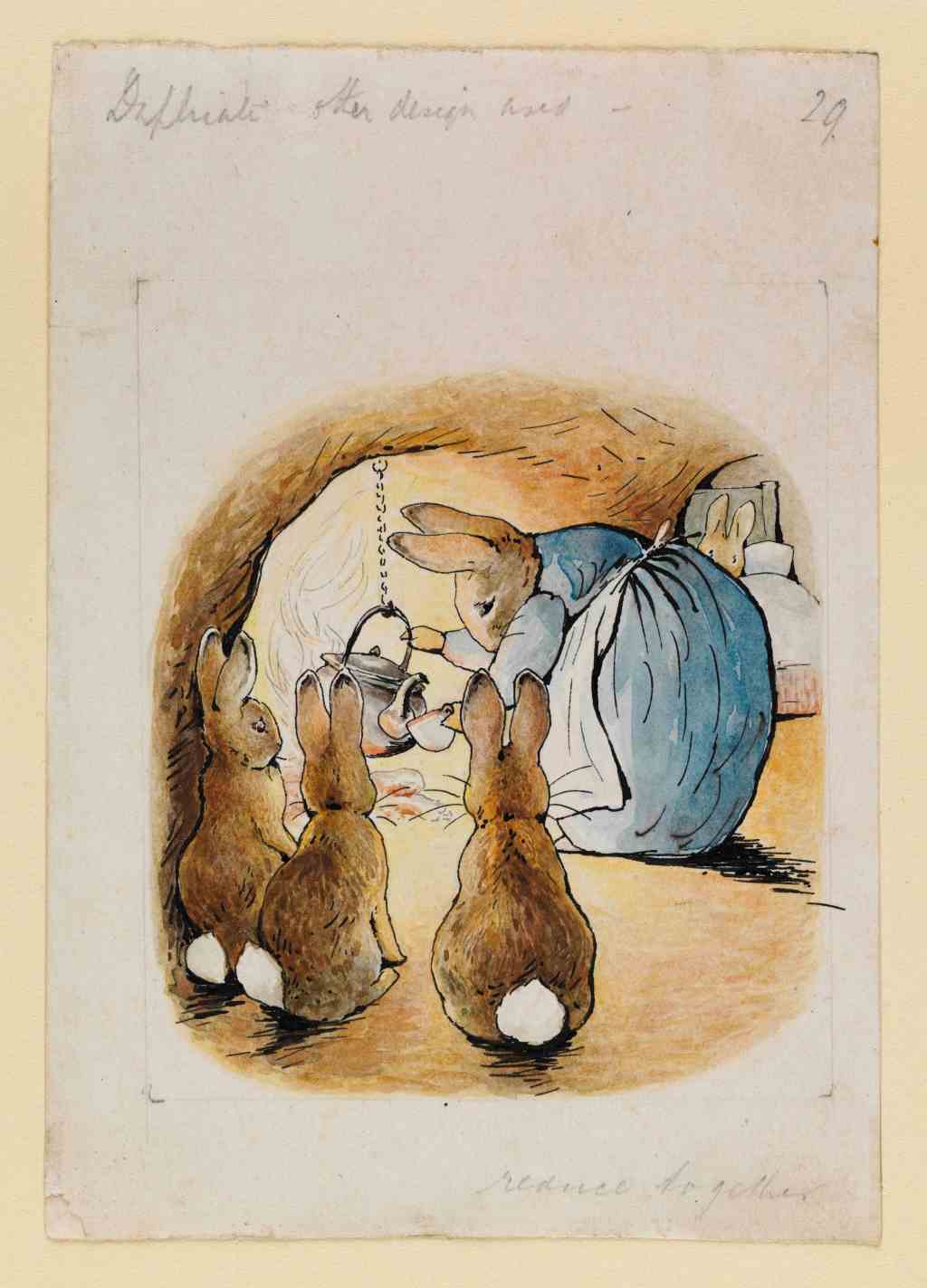

Now, 81 years after her death, Potter’s prismatic life continues to be celebrated. The Morgan Library and Museum in New York will unveil “Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature” on Feb. 23. Along with “Peter Rabbit,” visitors will find drawings of “Mr. Jeremy Fisher,” “Mrs. Tiggly-Winkle” and other characters from Potter’s classic children’s books. Other artworks, books, manuscripts, picture letters and artifacts mined from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Trust and the Armitt Museum and Library will be displayed through June 9.

Sarah Gristwood, who penned the biography “The Story of Beatrix Potter,” says, “These exhibitions are repaying a very old debt and a very old wrong, which is very important,” adding that many fans of her children’s books are in the dark about the third chapter of her life as a farmer and conservationist. Integral in the development of Britain’s National Trust in its early days, Potter bequeathed 4,000-plus acres to it.

Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), Spring, Harescombe Grange, Gloucestershire, circa 1903. Courtesy Photo

Gristwood has drawn on Potter’s writings for “Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries” that is due out at the end of February in the U.K. and in the U.S. And Hill Top, Potter’s farmhouse retreat in the Lake District, recently reopened for the season with a “Tom Kitten” attraction and a newly restored 18th-century window that was referenced in her 1908 book “The Tale of Samuel Whiskers.”

While “Peter Rabbit” and “Tom Kitten” make many think, “’Oh, how cute,’” Gristwood says, “Animals in her books never know if they’re going to be greeted as friends or eaten, basically. Think of Mr. Fox and Jemima Puddle-Duck and Peter Rabbit’s father being put into a [rabbit] pie. That blend of toughness and cuteness makes them still viable and huge to this day.”

Potter’s tales of animals with human characteristics have appealed to generations of readers in different ways. The accuracy of her animal illustrations, especially their muscularity is another reason for the stories’ longevity, according to Gristwood, who says that Potter boiled down skeletons to study them. She made a habit of taking her pet rabbit for walks on a leash too. Nevertheless, Potter was also coolly matter-of-fact about how her father planned to sell one of her favorite carriage horses to the London Zoo for meat. In listing how the payout varied based on weight, Potter made the distinction, “Thin ones not taken, as the lions are particular.” Many would see such partings more direly, given the demise of what they might describe as “a cute, lovable friend,” Gristwood says.

Far from an overnight sensation, her first book, “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” started out as a picture letter to a sick child in 1893. After being rejected by some publishers, Potter resorted to self-publishing it in 1901. A year or so later, after retooling her illustrations into color instead of black-and-white at the request of editor Norman Warne, the book was published. After six printings within the first year, the book’s popularity only gained ground from there.

Her prowess for merchandising — stemming from being the offspring of a “very well-to-do manufacturing family,” contributed to that, Gristwood says. The industrious Potter designed greeting cards before venturing into children’s books. Films related to her work are still being made today, Gristwood says. “It just goes on and on and on.”

Born in the summer of 1886, Potter, like Florence Nightingale, “had a long, extended pupillage as a young, unmarried women at home, which in Victorian upper-middle class circles meant effectively as an eternal child,” Gristwood says. She notes how with Potter’s “humorous, quite affectionate and unsparing eye,” the fact that fungi is seen by many as “cute, lovable and pretty,” was one draw for Potter but she was more compelled by their mythological associations and the many areas that were left to explore. “She, of course, became quite interested in the great mystery off how fungi reproduce.”

She wrote nearly all of her children’s books between 1900 and 1913, the same year she married William Heelis. Years before, her engagement to her publisher Warne ended tragically when he died unexpectedly. Gristwood says, “First, there was the Victorian daughter at home, doing her work on myclogy. Then there was the author of the children’s books and then as ‘Mrs. Heelis,’ the farmer and the conservationist.”

Philip Palmer, curator and department head of literary and historical manuscripts at the Morgan Library and Museum, highlighted in an email how unlike William Wordsworth and other Lake District-based writers, Potter “actually worked the land, raised sheep and preserved the environment for future generations.”

Visitors to the soon-to-open exhibition will learn how nature shaped Potter’s life and work, “from her childhood experiences in the countryside to her scientific interests in mycology and anatomy, through to her later career as a sheep farmer,“ Palmer says. “They will learn how her beloved tales for children are rooted in a fascination with real spaces and places, from the surroundings of her London home to her holidays around Britain and her Lake District farmhouse.”

Understandably enthusiastic about all things Potter-related, Gristwood’s hope is that those who return to Potter’s children’s books as adults see them as the tip of an iceberg and then delve into into her trove of natural history studies, her “brutal streak of realism,” how she overcame depression in her youth and the conservation work she did in the Lake District as a farmer and conservationist.

However revolutionary Potter’s life might appear to be, Gristwood says, “I don’t think she saw herself as a natural rebel or one, who wished to defy the standards of the day. It’s just that in her rather extended early life, as a young woman at home, she didn’t find it easy to conform to the norms that were expected of her.”