Fashion designer Stevie Edwards, who designed for such celebrities as Tiffany Haddish and Diana Ross, died Sunday in Chicago.

Edwards, 58, succumbed to colon cancer at a Warren Barr rehabilitation center, according to one of his sisters, Aretha.

Funeral arrangements are now being planned.

Last month the designer announced via Instagram that he planned to take a six- to eight-month break from designing, “depending on the healing process.”

Having been fighting cancer since 2021, the Chicago-born creative had returned to his home city for treatment. Prior to his diagnosis, Edwards, who had worked in fashion for more than 30 years, had divided his time between Chicago and Los Angeles.

During his three decades of experience, Edwards’ good fortune arose through red-carpet dressing and the unexpected generosity of a longtime client, who preferred to be a silent investor, and offered to pay for ads in Vogue, GQ, W and Harper’s Bazaar in 2020.

Needless to say, he had thought that that proposal was a joke. But after doing some research, Edwards had agreed to a meeting. The Houston-based marketing executive flew to Chicago for a dinner with the designer at a Gibsons Steakhouse.

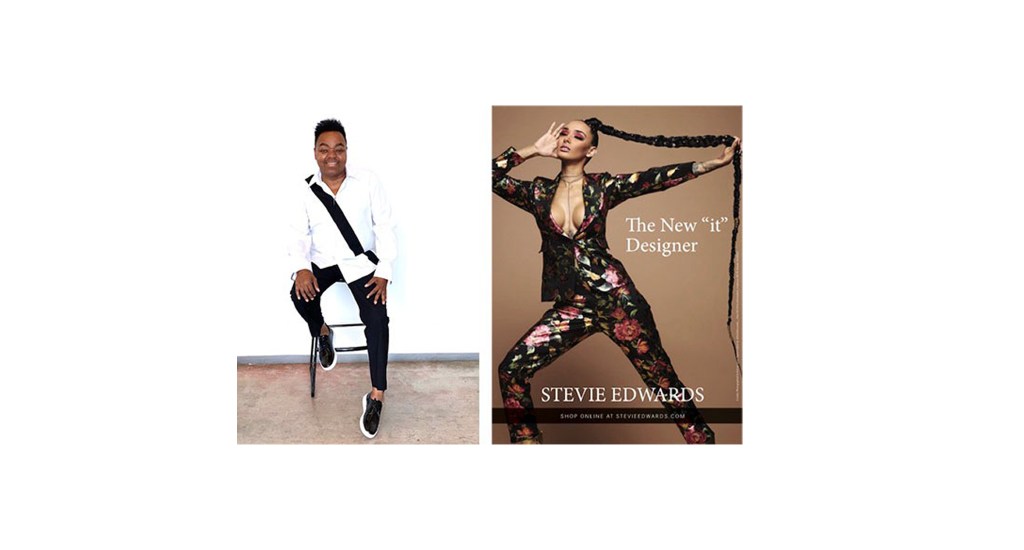

Eager to enhance his profile, she paid for a few ads in major magazines, including a full-page ad in a Los Angeles regional issue of Vogue. In a 2020 interview, Edwards claimed that he was the first local Black designer to have a full-page ad in the magazine. A model wearing one of his black floral pantsuits was featured with the tag line “The New ‘It’ Designer” and his name in capital letters.

The ad ran in the October 2020 issue, which featured the Grammy winner Lizzo on its cover, which was then a first for a plus-size Black woman. The designer told WWD at that time, “I’m making history in the same issue.”

The advertising helped Edwards, who for the most part worked independently, gain national attention. Speaking of his silent investor, Edwards had said, “I guess I’ve been complacent. I’ve been designing for over 30 years. But she told me, ‘You need to be bigger than this. The world needs to see you.’”

All in all, Edwards’ designing career was “his world. That’s what he lived for,” his sister Aretha said Monday. “All these celebrities like Tiffany Haddish were not just celebrities. They were his friends. That was Stevie’s heart. What hurt him most was when he couldn’t continue his career. He hadn’t been able to do that was since the first of this year.”

While attending Dunbar Vocational Academy, Edwards learned tailoring before venturing on to study fashion design and graduate from what was then called Ray-Vogue College of Design, before being renamed the Illinois Institute of Art. It was there that Eunice Johnson, a force behind Jet and Ebony magazines, discovered his eveningwear and bought a few of his creations for the International Fashion Fair Show that was organized through the Johnson Publishing Company. That recognition later led to Edwards appearing on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show.

Before starting his own company, Edwards worked for local Chicago designers Barbara Bates and the late Reginald Thomas. Over three decades, Edwards worked on music videos, weddings, direct-to-consumer, and had his own store at one point. Edwards launched the “I Luv Stevie” label in 2008, sold online, and worked with private clients by appointment and with stylists, including Law Roach. As is often the case in fashion, Edwards’ personal attire was often black and “Fabulous” was a favorite expression.

As the youngest of 10 children, Edwards’ siblings were overjoyed with his success. Raised on the South Side of Chicago, Edwards’ father was a longtime employee at the Libby’s factory and his mother oversaw the busy household. Aretha Edwards recalled Monday, “When we were growing up, it was a nice environment. As kids, we were able to go out and play without having to worry about the issues that young kids have to worry about today. There weren’t any drive-by shootings or any of that. We were able to jump rope, go outside, play ball. Our parents didn’t have to worry about us, so our childhood was wonderful.”

Darlene Edwards-Griffin added, “We lived childlike.”

Growing up, Edwards would talk about clothing with one of his brothers, Donnie, who was not a designer, but who was a man of fashion, according to his sisters. The youngest, Edwards later passed that on to the next generation by mentoring one of his nephews, LaShawnn David Edwards. The latter is a full-time public school employee, who pitched in at Edwards’ company and also has his own collection on the side.

Off-hours, the designer liked to relax by mingling with family and friends often in each other’s homes or sometimes out for dinner. His relatives have not yet discussed plans for his business. They recently discovered that he had been at work on a book, “Behind the Seams as a Designer,” which they hope to publish.

“Stevie felt that he had reached the top of where he wanted to be, and he just wanted to carry on. He thought he would get well, but he got sicker. He still thought before he died that he had reached the top of his career,” Darlene Edwards-Griffin said.

Edwards was predeceased by a sister Sheila and his brothers Clifford, Craig and Robert, who was known as “Pucci.” The designer is survived by his sisters Brenda, Aretha, Darlene Edwards-Griffin and his brothers Donnie and Glenn.

In lieu of flowers, his relatives requested that donations be made to the Robert H. Lurie Cancer Center at Northwestern University or to the designer’s GoFundMe page that had been started to cover his round-the-clock care and treatment and will now go toward the services that are being planned.