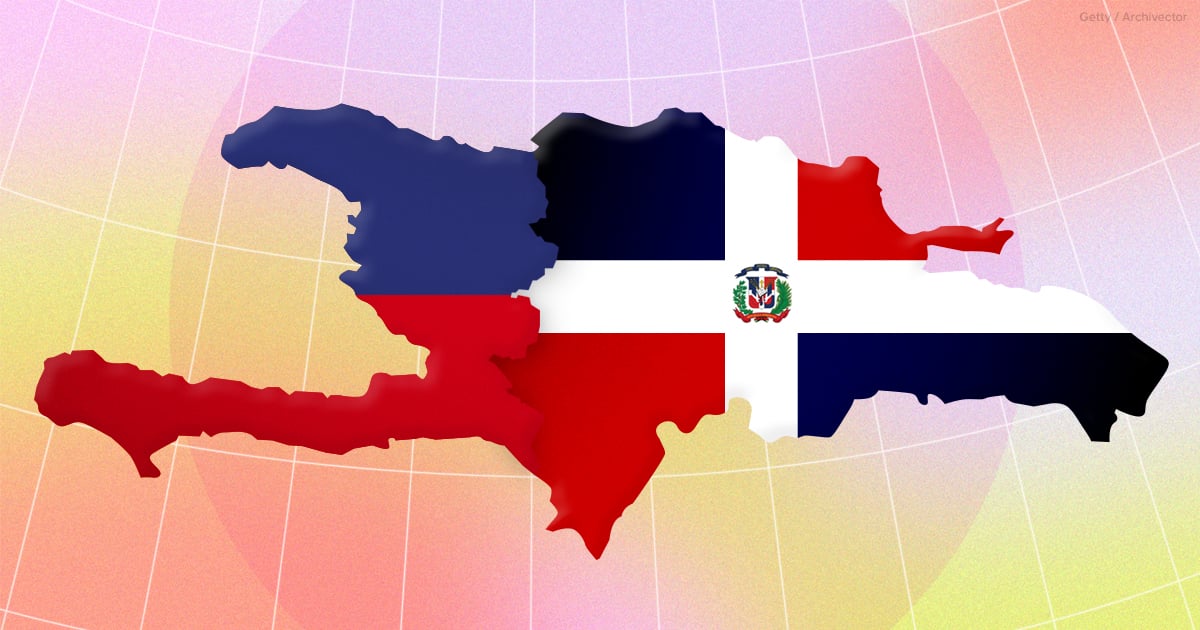

On Sept. 15, the Dominican Republic closed all entry points along its border with neighboring Haiti. This was Dominican President Luis Abinader’s response to a group of Haitian farmers’ construction of a canal drawing water from the Dajabón or “Massacre” River in the northwestern region of the island.

The closing of the border is an echo of a long-standing narrative that the Dominican Republic is the resource-rich part of the shared island and Haiti, its under-resourced counterpart, is forever attempting to violently siphon said resources. Not only is this a warped tale, but it also amplifies notions of anti-Haitianism and anti-Blackness within Dominican society, which President Abindader recently denied during his talk at Columbia University’s World Leaders Forum earlier this month.

As a Black queer Dominican who grew up in New York City, I’m no stranger to the realities of homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, colorism, racism, and anti-Haitianism that exist within Dominican culture(s). For those who may read the previous sentence and write me off because I wasn’t born in DR or did not grow up there, I invite you to hold space to understand that like the people who migrate, so do the cultures they bring with them that influence their descendants.

Having grown up around one of the largest populations of Dominicans outside of the country, I’ve gotten more than a taste of the culture(s) that have migrated beyond its shores. This includes the embedded hate – as much as the love. As someone who has traveled to and spent time in almost 25 countries and five continents in the last 15 years, I’ve come to develop a broad lens on how these forms of hate show up in various parts of the world. Through my own family and organizing work with Dominicans in the diaspora and on the island, I have listened to countless firsthand testimonies about the reality of not just being of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic but being Black (particularly dark-skinned) and what comes with that embodiment.

So you can’t write me off when I say that not only is there the existence of anti-Blackness and anti-Haitianism in the Dominican Republic and embedded deeply in Dominican culture, but it has also come at a great human cost for an island that consists of an overwhelming majority of Black people and people of African descent.

The recent events at the border are more ticks on the long timeline of the erasure and removal of Haitian folks and Dominicans of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic. Sept. 23 marked the 10th anniversary of a governmental resolution that effectively denationalized more than four generations of Dominicans of Haitian descent who are still fighting for pathways to citizenship in the only place they’ve known as home.

In this last decade, the Dominican state has only further doubled down and ramped up the forceful, traumatic, and violent deportations and mistreatment of Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian migrants.

The cultural realities that have led to the border closings and ongoing deportations reach further back than 2013, though. The history of Haiti and the Dominican Republic is complex and rooted in forces that have shaped so much of our world – namely, a small minority of white people who have tried to consolidate their power.

I understand it can be difficult to parse what’s happening right now, but it’s important to do so. Below, we break down some of the history and hear from a few people who have firsthand knowledge and expertise of these deep divisions.

How Anti-Blackness Took Hold in Dominican Culture

The border closing is rooted in what more progressive Dominicans and others understand as a made-up historic narrative of Haiti in relation to the Dominican Republic. It is rooted in what Altagracia Jean Joseph, a lawyer, an activist, and founder of Fundación Código Humano, describes as a history of blanqueamiento. This is the whitening of a people – and of white supremacy – that can go as far back as the often romanticized and inaccurate retelling of Dominican independence in the 19th century. The history has been decorated with anti-Haitian sentiments and goes even further back to the centuries of Spanish and French colonial rule that enslaved Africans and their descendants. This version of history is what often solidifies the justification for this specific type of hate.

“[This is] an ethnic persecution or [an] anti-Hatianismo more than anything, because there is also no admission that in the Dominican Republic, there are Black citizens who are not Haitian or of Haitian descent,” Jean Joseph tells POPSUGAR.

Famously self-proclaimed as the first independent Black nation, Haiti won its war for independence from France on Jan. 1, 1804. With the understanding and belief that liberty was a human right, Haitian revolutionaries went all over the world in solidarity to fight for the freedom of enslaved Africans. The Dominican Republic as its neighboring country was, of course, one of the places Haitian revolutionaries went to secure the sovereignty of their own newly formed nation and the eradication of all colonial rule on the island. The history is not commonly told this way (on or outside the island) and for more than two centuries has been misrepresented as one where Haiti exclusively wreaked havoc on Dominicans and caused harm to its society, government, and people. It would be romantic to say there has never been conflict between these two nations, but it would be more accurate to say the island’s history is older than that of colonial rule.

Sociocultural anthropologist Amarilys Estrella, PhD, recalls the history of the two nations differently from what is often framed as the “official” story. With reference to the research of Dominican scholars such as Ginetta Candelario – whose work deeply explores what constitutes national Dominican identity through a historical and social lens – and Lorgia García Peña‘s research on Black Latine lives at various intersections, Estrella recalls that part of the foundation of the historic tension between these two nations has been influenced by the gaze of white European travelers and their recorded stories, which inaccurately distinguished the two nations as one being a Black republic (Haiti) and the other an exoticized nation of mixed-race people (Dominican Republic).

“That history becomes erased in this process of creating these narratives of what these nation states are and can become.”

This is in tension with what Estrella points out: the Dominican Republic is home to the first port for enslaved Africans in this New World experiment. “That history becomes erased in this process of creating these narratives of what these nation states are and can become,” Estrella tells POPSUGAR. She argues that this perspective is fueled by the desire and demand for the exploitation of Black people, be it Dominicans of Haitian descent, Black Dominicans, or Black Haitian migrants.

The narrative within the Dominican imagination that Haiti is Black and the DR is anything but that has allowed seeds of hate to grow. That type of reasoning justifies false beliefs held by many conservative Dominicans of Haitian invasions and anything Haitian as the complete downfall of Dominican society.

One of the most glaring examples of this happened 10 years ago. On Sept. 23, 2013, the Dominican government issued Judgement 168-13, which retroactively denied citizenship to anyone who did not have at least one Dominican parent (by blood) or was otherwise undocumented. This ruling was on the heels of laws as far back as the early 2000s that expanded the opportunity for children of Haitian migrants to be denied citizenship.

Aside from legal precedents to harm Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian migrants, the deeper issue is societal treatment. Again, if the Dominican imagination is more preoccupied with what it is not than what it is, it becomes easier to deny the reality of the history between these two nations, which has countless examples of community building, collaboration, and coexistence.

How Can Haiti and the Dominican Republic Move Forward?

So what can be done about this? First, acknowledge where you are positioned within this conversation. For example, as a light-skinned Black person, I strive toward being as mindful as possible of the space I take up and where (in Black spaces especially). If you are Dominican and reading this piece, there is a chance you are part of the nation’s long-reaching diaspora, outside of the island. That is important to name because, like culture, bias travels with people. The anti-Black and anti-Haitian sentiments discussed here exist far beyond the shores of the first colonial experiment in the West. I also want to be clear that the key shifts in this struggle will come from within the island. For folks in the diaspora, it is our job to follow that lead – not the other way around.

From that place, as with most social issues, the work can start with people closest to us: our family and friends. Revolution and societal change occur over the course of many nights, not one. Personally, I have been in an almost two-decades-long conversation with some of my closest family members around these issues, and though we have come to a more unified understanding, there is still much work to be done in the unlearning of these incredibly cemented views.

This also calls for Dominicans to be with the harshness of the anti-Blackness and anti-Haitianism we are taught from the moment we leave the womb. It means naming the ways these racist ways of thinking overlap with sex, class, gender identity, sexuality, ability, and all the elements of a person’s being that may or may not get protected by laws.

In addition to the important interpersonal work of challenging and pushing each other on our ways of thinking and treating anything read as Black or African, we can also support ongoing efforts that address these issues, such as Jean Joseph’s Fundación Código Humano, which serves DR’s “invisible population” (i.e. victims of rape and sexual assault, LGBTQ+ Dominicans, poor and working-class Dominicans, etc.) as well as grassroots organizations like Reconoci.do, Acción Afro Dominicana, Incultured, Co, Muñecas Negras RD, MUDHA, and Diversidad Dominicana, to name a few.

These anti-Black and anti-Hatian sentiments, legal systems, and nation-states are not insurmountable if we are willing to use whatever power we may have to address them, collectively. If all you accomplish is getting a loved one to see these issues with more compassion and understanding, you have done important work. And for those with more capacity, that is vital, too. It will take every level of change to cause the radical shifts necessary to put an end to this history and practice of hate.