It’s common to think of Serena Williams or Naomi Osaka when it comes to people who have changed the game of tennis in profound ways. What you don’t hear about as much is the people who sit up in a chair and see the game from a different perspective, making the key calls on the matches that can secure a tennis pro’s victory: tennis umpires. These professionals have historically been predominantly white and male, but now more than ever, women tennis umpires are making strides. There are currently 13 women umpires, out of 35 total umpires on the elite match level. They’re paving the way by being visible at global events like the Olympics and grand slams, and mentoring other women to move up the officiating ladder.

But the industry hasn’t always been so inclusive – and there’s more work to be done when it comes to equity and representation. Though women’s tennis as a sport has grown tremendously over the years, with women’s tennis at the 2023 Tokyo Summer Olympics surpassing men’s tennis in viewership, male umpires are more likely to be chosen to umpire men’s finals matches, by a landslide. In fact, men are also more likely to have a gold badge, the highest level of umpire certification, which allows them to be an umpire for Grand Slam tournaments like Wimbledon and the French Open, or for the Olympics. Data published in 2017 by the Journal of International Women’s Studies reported that 72% of umpires with gold badges at that time were men, compared to under 28% of women gold-badge holders. When you add race and ethnicity to the conversation, the numbers become even more dire. For example, there has only ever been three Black (male) gold badge-holding umpires in the entire International Tennis Federation (ITF), a global tennis organization that’s been around since 1913, and Sande French remains the only Black women to have worked as a professional chair umpire in the US.

Why Is There Such a Discrepancy in the First Place?

The road to elite level tennis umpire is no easy feat. Becoming a gold-badge holder in the US can take a decade, in which you must get USTA certified, officiate lower-tier matches, attend seminars, pass written tests, and undergo ITF evaluations, per Forbes. There are also three other tiers before you reach gold – white, bronze, and silver – each with their own requirements for passing.

Other barriers to getting the gold badge can include how much support an official receives from their local tennis federation or local tournament’s governing body at the early levels of their careers; how broad their experience ranges across various regions and levels (this can also depend on how many events the official applies for and is successfully accepted to officiate); how frequently they officiate; and how they perform in their evaluations. Needing to support a family and having to travel across the world more than half the year to referee enough matches to do so is an additional challenge, according to umpires.

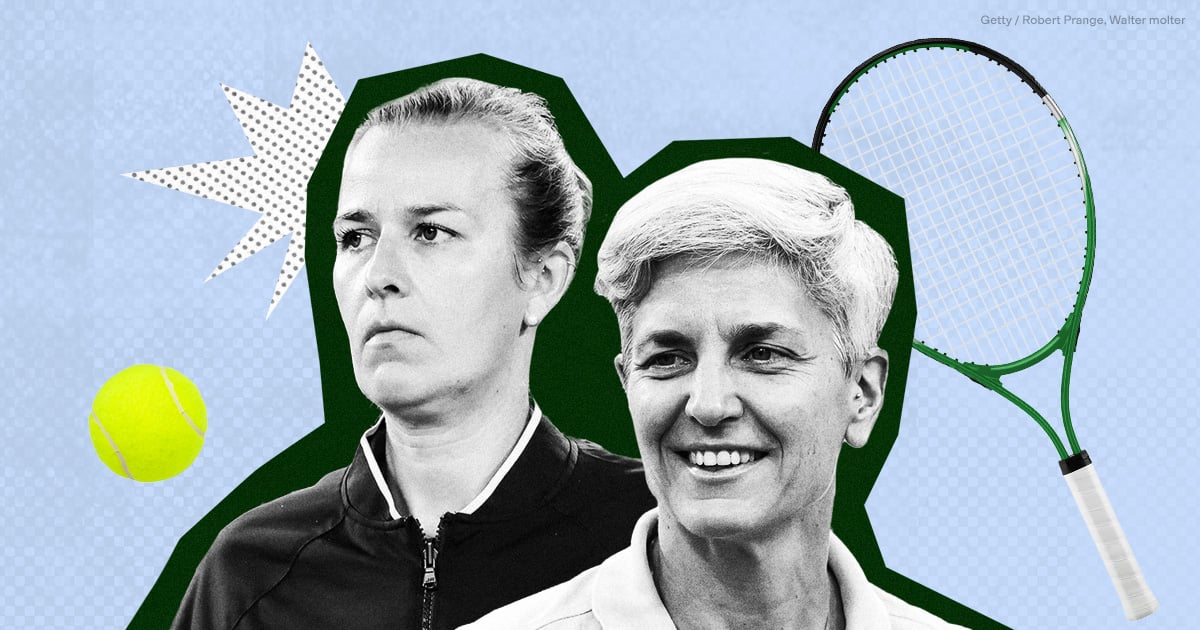

In some cases, even when you have the badge, you still don’t get the job. Marija Čičak, for example, has had a gold badge since 2011, granting her an international certification with ITF. But it wasn’t until 2021 (over 10 years later) that she became the first woman to chair umpire a Wimbledon men’s singles final (for reference, Wimbledon has been around since 1877). “I had to put it in my head that it was another match that I had to do,” Čičak tells PS of her mindset during the game. “But it wasn’t another match.” There was history being made, Čičak says.

Čičak has been refereeing full time since the age of about 25 and on the road for 25 or 26 weeks of the year, but this can be significantly more challenging for women umpires who are simultaneously raising families, she says. Čičak reports that the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), and its male counterpart, the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), now encourages women umpires to participate in their entire tours, even if they have families and need to bring small children along in order to participate in as many matches as they can.

Nationality also plays a role in the selection process, in addition to the umpire’s experience with the players. “If the final is Federer versus Nadal, a Swiss or Spanish umpire won’t get the call. From there, experience is considered: Who has already handled those particular players?” Forbes reports.

What’s Being Done to Improve Representation and Equity?

For starters, mentorship has become a crucial part of the process. Miriam Bley, the first women umpire from Germany to earn a gold badge, feels a drive to give back to other umpires from her country in the hopes of bringing more women into the fold. She’s been part of the WTA’s umpire development program since she started as an umpire, and is now (along with Čičak) part of the WTA and ATP’s official joint mentorship program, which crystallized in 2021.

“When I started umpiring, there were not many females around,” Bley tells PS. “The mentoring program is amazingly important, so that I can give back what I have received.”

“We need mentors; we need people we can rely on,” she tells PS. WTA’s umpire mentorship joined forces with the men’s ATP in order to promote both women and men officials in both women’s and men’s tennis, mentoring each other. Čičak is currently in charge of the silver badge mentorship program, which enrolls younger officials for a full year to guide them a path toward success at their current level and making it to the gold badge level.

The WTA also claims to be working on improving its overall diversity, equity, and inclusion. “One of the ways the WTA remains committed to its founding principles of equal opportunity is the WTA Foundation, a vehicle created to change lives by advocating for equality regardless of gender, age, race, nationality, disability, beliefs, or sexual preference, promoting education, supporting leadership pathways, and ensuring health and wellness worldwide,” the organization said in a statement to PS.

On the gender equity front, the ITF has made a strong commitment to appoint equal numbers of men and women umpires for this month’s upcoming Paris Olympics and Paralympics. Joining the team as a chair umpire this year will be Bley, who previously worked at the 2012 Paralympics in London, the 2016 Rio Games, and the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. Though official assignments of matches each umpire will cover remain to be seen, the most important thing is that the ITF is striving for gender parity (even though there are fewer women gold badge umpires than male gold badge umpires to begin with), Čičak points out.

The WTA, for one, wants to continue the momentum of more representation for women going – they’ve appointed two women CEOs in the past year, one overseeing WTA Ventures, Maria Storti, the other assuming the role of CEO of the WTA Tour, Portia Archer. Along with the mentorship program for bringing more women umpires into the game, the WTA hopes to expand its ongoing Coach Inclusion Program, promoting more women in coaching. The WTA, led by legend Billie Jean King, has committed to awarding women tennis players completely equal prize money to men in major tournaments, but evidence suggests this won’t be fully equivalent until 2033.

“Numbers are definitely shifting. We are going in the right direction of achieving this equality,” Čičak tells PS. “There are more and more chances that we are giving to upcoming female officials, to get to have careers that in the past we could only dream of.”

Mara Santilli is a PS contributor, freelance writer and editor specializing in reproductive health, wellness, politics, and the intersection between them, whose print and digital work has appeared in Marie Claire, Glamour, Women’s Health, SELF, Cosmopolitan, and more.